The Coming of Jesus: Revelation Fulfilled?

Series Index

- The Coming of Jesus: Introduction

- The Coming of Jesus: Daniel's 70 Weeks

- The Coming of Jesus: Coming on the clouds

- The Coming of Jesus: The Olivet Discourse – Part 1

- The Coming of Jesus: The Olivet Discourse – Part 2

- The Coming of Jesus: Revelation Fulfilled?

- The Coming of Jesus: Our Future Hope - What Now?

Don’t let the title put you off, we’re about to go on a mad journey through the annuls of history and the Roman Empire, contrasting what John saw in his vision with what has already played out on the “world’s stage” and what we possibly have to look forward to!

First though, let’s look at a little history concerning the book itself before delving into its contents. Why do this? For a couple of reasons really: one, Revelation has some dispute over the year in which it was written, which can impact on the interpretation. Two, at various points in early church history, the book was held in suspicion of being spurious and almost didn’t make it into the Canon of Scripture. We should always endeavour to understand the history and context of a book of Scripture in order to fully understand its intended meaning, and thus, “rightly divide” (2 Tim 2:15) and interpret the Bible properly.

Two Dating Views

There are two main views on the dating of Revelation: the “early date” and the “late date”.

The early date places John writing Revelation around 64-68 AD, shortly before the fall of Jerusalem and just as the Jewish War was getting underway during the reign of Nero.

The late date puts the writing towards the end of the reign of Domitian around 95-96 AD.

From John’s own testimony, we know that he was suffering persecution at the time of writing:

Revelation 1:9

I, John, your brother who share with you in Jesus the persecution and the kingdom and the patient endurance, was on the island called Patmos because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.

Both of these Roman Emperors persecuted the Christians, though none quite so severely as Nero did.

There’s varying accounts of when Revelation was penned by John. I won’t spend too much time on this as many, many others have wrote books on the topic of dating, so I’ll just give a brief overview of both sides of the argument.

One of the earliest accounts mentioning a possible early date for Revelation is from the “Muratorian Fragment” which dates back to the around 170-190 AD. This fragment is one of the earliest lists we have of the accepted Canon of Scripture (or books which were approved to be read in the Churches), and in it there is a curious sentence about Paul “following the rule of his predecessor John, [writing] to no more than seven churches by name.” This is interesting because Paul’s letters are widely accepted to be amongst some of the earliest New Testament books we have, as well as historical tradition and writings saying that Paul was martyred under Nero’s reign around 67 or 68 AD, which means if he followed “his predecessor” John, Revelation must have been written before 70 AD!

There’s also one other reference which offers some insight (though is quite hard to find many sources on), in which the Syriac Vulgate Bible from the sixth century has an opening title to Revelation as follows: "The Apocalypse of St. John, written in Patmos, whither John was sent by Nero Caesar."

The late date theory is mainly due to a single quote by Irenaeus (plus a couple of other historical references about John which indirectly impact the early date), where he somewhat cryptically mentions John and/or his vision as possibly being seen during Domitian’s reign:

“We will not, however, incur the risk of pronouncing positively as to the name of Antichrist; for if it were necessary that his name should be distinctly revealed in this present time, it would have been announced by him who beheld the Revelation. For that was seen no very long time since, but almost in our day, towards the end of Domitian's reign." — Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.30:3

What exactly Irenaeus was referring to being seen “almost in [his] day” has been questioned over time due to the cryptic nature of the sentence, and because just a few paragraphs before this statement, he refers to “ancient copies [of the Apocalypse]” implying the actual text is older than his time.

Eusebius, in mentioning this in his Church History (III, ch. 18), phrases this as: “almost in our own generation”. This potentially changes the way in which you could read Irenaeus’ statement, as it could be understood as saying: ‘almost in our day (the generation towards the end of Domitian’s reign), the revelation was seen.’

The part about Domitian’s reign could just be a way to further clarify the time Irenaeus was living in, rather than specifying the time when John saw the revelation, which was only seen “almost in [their] day” – but not quite in their time! This would then reconcile better with Irenaeus also referring to “ancient copies” of John’s Revelation.

Robert Young (of Young's Concise Critical Bible Commentary) also challenges this late date:

"It was written in Patmos about A.D.68, whither John had been banished by Domitius Nero, as stated in the title of the Syriac version of the Book; and with this concurs the express statement of Irenaeus (A.D.175), who says it happened in the reign of Domitianou, ie., Domitius (Nero). Sulpicius Severus, Orosius, &c., stupidly mistaking Domitianou for Domitianikos, supposed Irenaeus to refer to Domitian, A.D. 95, and most succeeding writers have fallen into the same blunder. The internal testimony is wholly in favor of the earlier date."

Concise Critical Comments on the Holy Bible, by Robert Young. Published by Pickering and Inglis, London and Glasgow, (no date), Page 179 of the "New Covenant" section. See also: Young's Concise Critical Bible Commentary, Baker Book House, March 1977, ISBN: 0-8010-9914-5, pg 178.

There is another theory on the conflicting dating by a David E. Aune, which states that John wrote his apocalypse in two parts. The first during Nero’s tyrannical reign and persecution of the Christian Church around 68-70 AD, and the second “edition” towards the end of the first century. He suggests this, not only based on the themes of persecution in the book, but also because there is a lack of external historical evidence for such dramatic persecution near the end of the first century. The other reason for this dual-dating is the the way in which John writes about Jesus. According to Aune, John later gives “titles and attributes normally reserved for God in Judaism … to the exalted Christ.” (Reclaiming the Book of Revelation, W. E. Glabach, p.36)

The details of who persecuted John and exiled him as a result, seems to predominantly point to Domitian, although there are still varying references in early writings which also point to it being Claudia, Nero or Trajan (Patmos in the Reception History of the Apocalypse, By Ian Boxall, p.31)!

Personally, with the external evidences, it makes me want to lean a little towards the late date, (although the alternate reading of Irenaeus’ quote I proposed earlier causes me to be less certain of a late date), but then the internal evidence of what Revelation contains and describes would appear to fit better with events of an early date pre-70 AD.

If the late date be true, maybe John was recapping earlier events through a spiritual lens, and then following on with the persecution that happened under Domitian’s rule and the eventual demise of the Roman Empire? I won’t be too dogmatic about it either way.

Four Interpretation Views

As well as there being two different views on the dating of Revelation, there are as well, four different views of interpretation! These are: the Futurist View, the Historicist View, the Past Fulfilled View, and the Idealist View.

In brief, these four different views generally say this:

“The idealist approach believes that apocalyptic literature like Revelation should be interpreted allegorically. The preterist and historicist views are similar in some ways to the allegorical method, but it is more accurate to say preterists and historicists view Revelation as symbolic history. The preterist views Revelation as a symbolic presentation of events that occurred in AD 70, while the historicist school views the events as symbolic of all Western church history. The futurist school believes Revelation should be interpreted literally. In other words, the events of Revelation are to occur at a future time.”

Patrick Zukeran, probe.org

While all of this is interesting and possibly challenging for us reading Revelation today, it was unlikely to be so obscure and strange to the early church and those in the seven churches of Asia addressed in the beginning chapters. An “apocalypse” – as in, the genre of writing style that Revelation employs, was fairly well known and accepted within Jewish culture and religion, as it lends heavily from Old Testament prophetic writings. Not only that, but the believer’s it was addressed to were expected to understand this letter just by it being read to them in their churches, as we can see from Rev 1:3 –

Blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of the prophecy, and blessed are those who hear and who keep what is written in it; for the time is near.

And so, we must try to interpret it in the same manner that the original audience would have understood it, with all of the historical circumstances and context that they were living in and through. It might also be worth noting here, more for informations sake than anything, that Revelation was, at one time, counted among the disputed books, though accepted by others to be genuine. So while it has become almost a staple within modern Evangelical doctrine of the “End Times”, it wasn’t always so (cf. Eusebius, Church History, Ch. 3:2; Ch. 25:4).

In terms of the Jewish War and the siege and eventual destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, Eusebius (along with other early writers, such as Tertullian and others) quite happily regard all of this as the fulfillment of all that Jesus prophesied, as recorded in Matt 24, Mark 13 and Luke 21, and also as the completion of the 70 Weeks of Daniel’s prophecy.

“It is fitting to add to these accounts the true prediction of our Saviour in which he foretold these very events … If any one compares the words of our Saviour with the other accounts of the historian concerning the whole war, how can one fail to wonder, and to admit that the foreknowledge and the prophecy of our Saviour were truly divine and marvellously strange.”

Eusebius, Church History, Ch. 7:1, 7

“Vespasian, in the first year of his empire, subdues the Jews in war; and there are made lii (52) years, vi (6) months. For he reigned xi (11) years. And thus, in the day of their storming, the Jews fulfilled the lxx hebdomads (70 sevens) predicted in Daniel.”

Tertullian, An Answer to the Jews, Ch. VIII, 160

Key Points

While initially I was beginning to wonder if Revelation had anything to do with the fall of Jerusalem or was about the later persecutions in Christianity, after studying this a lot more it would seem to be that John was speaking about the impending doom of Jerusalem as well as later persecutions and the fall of the Roman Empire which was, in nonspecific terms, “the beast” and specifically, individual Roman Emperors.

Revelation six especially appears to directly correlate with Matthew 24 with the predicted signs and woes which were to come. Matthew lays it out in “real world” terms, whereas Rev 6 speaks of the same things happening, but from the heavenly viewpoint of Jesus opening the seals on a scroll.

Let’s break it down a little:

|

Matthew 24 |

Revelation 6 |

Seal/Meaning |

|

vv.4-5: Jesus answered them, “Beware that no one leads you astray. For many will come in my name, saying, ‘I am the Messiah!’ and they will lead many astray. |

v.2: I looked, and there was a white horse! Its rider had a bow; a crown was given to him, and he came out conquering and to conquer. |

The first seal is a white horse with the rider in a crown. The symbolism of purity and honour is then eclipsed by the fact this horseman intends to conquer those he goes to. The wider comparison here is that of the White Horse of Rev 19:11 in which Jesus is the rider, showing more so this first horse is an imposter of truth. |

|

vv.6-7a: And you will hear of wars and rumors of wars; see that you are not alarmed; for this must take place, but the end is not yet. For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom... |

v.4: And out came another horse, bright red; its rider was permitted to take peace from the earth, so that people would slaughter one another; and he was given a great sword. |

The second seal/horseman is the red horse which brings with it war and removes peace. |

|

v.7b: …and there will be famines… |

vv.5-6: ...and there was a black horse! Its rider held a pair of scales in his hand, and I heard ... a voice … saying, “A quart of wheat for a day’s pay, and three quarts of barley for a day’s pay, but do not damage the olive oil and the wine!” |

The third horseman is generally understood to represent famine due to his imbalanced scales which he holds. The value of basic food is disproportionately high, and thus would cause famine – especially among the lower class and poorer citizens. |

|

v.7c: …and earthquakes in various places… In Luke’s version, Jesus also mentions there will be “famines and plagues” (Lk 21:11). |

v.8: I looked and there was a pale green horse! Its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed with him; they were given authority over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword, famine, and pestilence, and by the wild animals of the earth. |

The fourth seal also emcompasses famines, along with death in general by various other means. It’s possible that the preceding horseman is what sets things in place for Death to ride through, by affecting the economy enough to result in famine, which would lead to death along with much disease. |

|

v.9: Then they will hand you over to be tortured and will put you to death, and you will be hated by all nations because of my name. |

v.9: When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slaughtered for the word of God and for the testimony they had given |

The fifth seal is one which affects even God’s own people. This is the seal of martyrdom. |

|

vv.14-16ff: And this good news of the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the world, as a testimony to all the nations; and then the end will come. |

vv.12-13: When he opened the sixth seal, I looked, and there came a great earthquake; the sun became black as sackcloth, the full moon became like blood, and the stars of the sky fell to the earth as the fig tree drops its winter fruit when shaken by a gale. v.17: …for the great day of [God’s] wrath has come… |

This seal matches the same language and imagery as the prophecy in Joel 2, which Peter also quotes on Pentecost as being fulfilled in the pouring out of the Holy Spirit before the Day of the Lord fully arrived in the War against Jerusalem. |

You’ve then got the “beast” of Revelation which seems to have dual symmetry: one of representing specific Roman Emperors, and then again as representing the Roman Empire as a whole. Revelation 17 references the beast as having “seven heads” which are the “seven mountains” on which it belongs. These are also “seven kings”, five of whom have been and gone at this point. Rome is known to have been the city built on seven hills, so this appears to be what John is alluding to in his vision, which many scholars also agree on, along with the veiled reference to Rome being “Babylon”.

In this section about the seven kings, there is also mention of “ten horns” which you may recognise from Daniel’s vision in Dan 7 which predicted the main future kingdoms of the Earth’s history (Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece and Rome, which was the majority opinion of the Early Church, and can be see in Jerome’s commentary on Daniel). These also would correlate with John’s revelation about the seven kings as being the line of Roman Emperors.

But how does ten horns and seven kings match up, you ask?

Daniel 7 gives us a clue here as this vision adds a little detail which Revelation omits, but which history can fill in the gaps. Daniel 7:7 is about one of the beasts (a kingdom) with ten horns which was to come. This is now here in John’s day in the form of the Roman Empire. This is also why we can equate the “beast” of Revelation with a kingdom too, as this is how Daniel’s vision portrays ruling powers and the two books correlate closely with one another.

Then in the next verse we see that three of the horns are uprooted to make room for another, the “eighth king” which also “belongs to the seven” as Rev 17:10 tells us.

If we look at the line of Roman Emperors, starting with Augustus (the first official Emperor) we have:

Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus and Domitian.

Of all of these, Galba, Otho, Vitellius barely reigned. These three literally only lasted a few months each; none made even a single year in power due to being murdered and suicide.

So when you “uproot” these three, it leaves us with Emperors who had lengthier reigns and who made an impact on the Empire and on history in general (for better or worse!). So while Daniel makes note of the three being removed, John seems to skip by them and just focus on those in power that were important in the events being foretold.

When we view the references to the beast with this in mind, we can make some sense of it, as displayed below in the table:

|

The Beast |

“...was…” |

“...and is not…” |

“...and is about to ascend from the bottomless pit …” |

“...and go to destruction.” |

|

The Seven Kings |

“...five have fallen…” |

“...one is [reigning]…” |

“...the other has not yet come, and when he comes, he must remain for a little while…” |

“The beast that was and is not, is himself an eighth king, yet he belongs to the seven and is going to destruction.” |

|

The first Roman Emperors |

Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero |

Vespasian |

Titus |

Domitian |

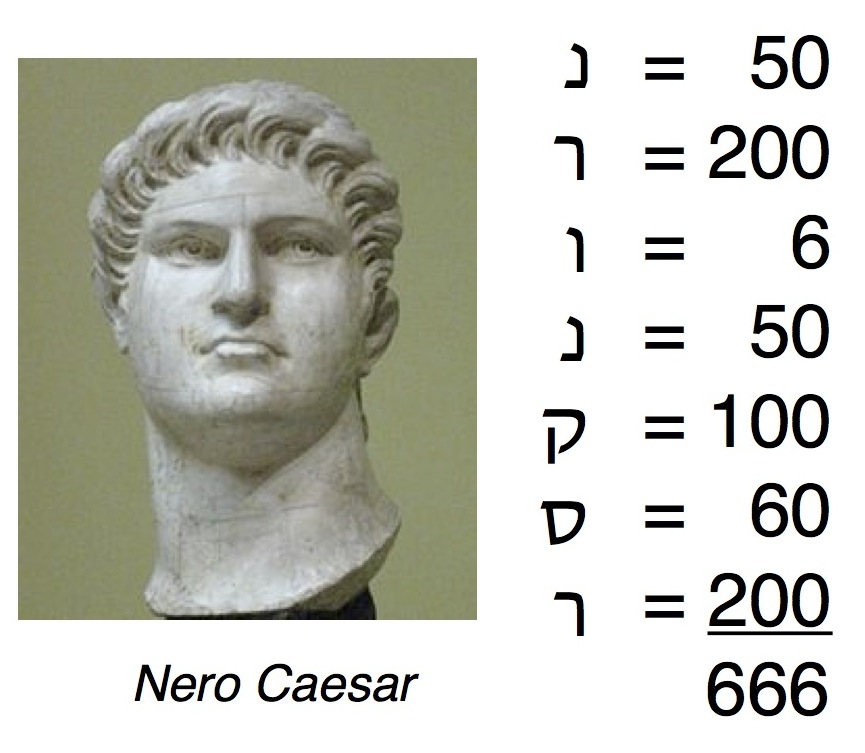

The beast that “was” I believe to be Nero. It is his name which best fits the decryption of the numeric name of “666” (translated as “Cæsar Neron” using the Hebrew gematria) and also due to his relentless persecution of Christians and his evil nature in general. Under Nero, Christians “were clad in the hides of beast and torn to death by dogs; others were crucified, others set on fire to serve to illuminate the night when daylight failed” (Tacitus, Annals, 15.44).

Domitian did also meet destruction in the form of an assassination by court officials.Then we have Titus, who did only remain a little while, reigning for only two years as Emperor. His reign was blighted with misfortune, such as Mount Vesuvius erupting and destroying Pompeii and surrounding towns, to one of the worst plagues known spreading through the Empire. Some believed this was punishment from the gods for his terrible treatment towards the Jews in the Jewish War and for destroying the Jerusalem Temple!

Alternatively, if Domitian is the “one who is” (if John wrote under his reign, rather than Nero’s) then that would make Trajan the 8th king and Nerva the one who comes for a little while (and did only reign for a year). Trajan also brought persecutions against the Church, so it is plausible on the face of it.

But this doesn’t fit with the three horns being uprooted (Galba, Otho, Vitellius) to make room for the short reign (Titus). Whichever it is, it still would apply to Roman rulers and the persecution done by the Empire. It also would be strange to only count the previous five, not beginning with the first Emperor, if there had been others before. So with that it makes sense to count the fallen five as the first emperors, starting with Augustus who was the first official Emperor in a monarchy-like position.

Other Interpretations

It's also worth noting that the early Reformers believed that the beast and kings/horns were a reference to the dark ages of 1260 years when the Popes ruled via a corrupted Church system out of Rome/Babylon. They tied their theology of the seven kings to different Popes and believed the antichrist to be the Papacy.

Another view, which relates back to the Roman Empire, comes from Jerome’s Commentary of Daniel in which he states that “[t]he fourth empire is the Roman Empire, which now occupies the entire world” but “when the Roman Empire is to be destroyed, there shall be ten kings who will partition the Roman world amongst themselves.”.

There is one other view worth mentioning, which is that John spoke of the kings as empires or kingdoms, rather than individual rulers. The five kings that "were" are those from Babylon to the Seleucids, the one that "is", was the (then current) Roman Empire, with a seventh that was still to come and an eighth which would arise from the seven.

Again, this also sounds a plausible interpretation. This could also be the wider application of Rev 17 and maybe there is also a longer reach to John’s vision other than just events local to him, as many Protestants and the Historicism doctrine teaches.

Historical Context

While the other views and interpretations possibly have some plausibility, I don’t believe it completely fits the context of Rev 17 where it mentions the “seven heads” of the beast being the seven mountains on which it sits, ie. Rome.

Other than that, we can read of the persecutions from early accounts written by Christians during these times and how they related Domitian’s rule to be like that of Nero and how he “possessed a share of Nero's cruelty” and “who dyed his sword in Christian blood”, as Tertullian wrote (Apol. 5.17). By this point, Nero was long dead but his cruelty wasn’t forgotten. The Romans feared that Titus was going to be like Nero when he came to power, due to his ruthlessness in war, but it was in fact his brother Domitian who turned the Empire back to harsher times.

This is where I believe the link to the beast comes from in Revelation. Nero was an archetype, the beast/antichrist first personified. But he was the beast that “was, and is not”, the one who began persecutions against the Saints. Now, again the beast “is about to come” in form of Domitian when he took power after Titus’ sudden death. Tertullian even described Domitian as “a limb of this bloody Nero” (Apol. 5.17)!

Both Nero and Domitian considered themselves divine – Nero even building a statue of himself in the pose/form of the Roman sun god, Sol. Domitian took it one step further and required everyone to refer to him as “lord and god” and also had money printed in this theme! This would be where Rev 13 fits in, I believe, with the mark of the beast and the image of the beast which was to be worshipped. Roman citizens had to pay homage to the Emperor, recognise his divinity and make sacrifices to him and the other gods of Rome on pain of death.

Eusebius doesn’t miss this connection either when writing his Church History, as in Book 3.18 he writes about John’s apocalypse and how he “accurately indicated the time” of persecutions which were performed under Domitian’s harsh rule. Chapter 19 and 20 of Church History also relate how the Emperor had all the “descendants of David” (Jews) killed and then those who were “the descendants of Jude” (ie. related to Jesus’ earthly relatives) “on the ground that they were of the lineage of David and were related to Christ himself.”. Eusebius mentions that “even those writers who were far from our religion did not hesitate to mention in their histories the persecution and the martyrdoms which took place” (Church History, Book III).

There’s then the link back to Daniel 2:41 and interpretation of the statue from Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, where Daniel say it will be “a divided kingdom” (due to the two legs of the statue). This is what later happened to the Roman Empire shortly before its fall; it was divided into an East and West empire, of which there was five countries or provinces in each.

The Western part: Britannia, Gallia, Hispania, Italia, Africa; and the Eastern part: Asia, Pannonia, Maoesia, Thracia, Asiana, Oriens.

Two legs, ten toes? Divided kingdom, ten kings? Two heads, ten horns?

To Summarise

The date of writing is debated. Some argue for pre-70 AD authorship under Nero or just after him, while others argue for a late 90s date in the reign of Domitian. Church tradition and other early texts do seem wholly in favour of the later date, from what I can see, though there is definitely internal evidence within the text of Revelation which would appear to be speaking of events before the Jewish War. But as always, these things are open for interpretation – even the quotes which appear to favour a late date, since the language is often obscure and no one explicitly stamps a date on when John first saw or wrote this book, just allusions to certain times.

The early chapters and church letters seem to be writing pre-70 AD, sometime in the reign of Nero. Apart from the Jewish War with the Romans, there was no other persecution (especially against Christians) until Domitian and beyond.

Revelation 2:9 and Rev 3:9 appear to be talking about Jews who were persecuting the Church, but after the fall of Jerusalem, there is little to no evidence that the Jews went after the Christians anymore. This was mainly carried out by Rome after the war.

Later chapters talk about the saints who die in the “great tribulation” (Rev 7:9, 14) and about the temple being no more as God now dwells with his people in the New Jerusalem. Though this could be a hindsight text, writing of the previous persecution under Nero and the War and the spiritual events behind it – especially since John was told to measure the temple prior to this, and that the “nations” would trample the Holy City (Rev 11:2) which is what Jesus predicted in the Olivet Discourse (Lk 21:24), and that event was pretty much unanimously agreed upon by the Early Church writers to have been fulfilled in the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

Revelation is also warning the Church that more is yet to come, and possibly is referring to yet another Jewish War: the revolt of Bar-Kokhba, which interestingly, also lasted just over 3 years too, along with the general persecutions against the faithful.

Chronology isn't a strong point in this book, it jumps around a lot. The last few closing chapters seem to be slightly sporadic, almost like isolated events disconnected from the previous narrative, which could be speaking of something future. Many of the Early Church Fathers believed and expected a literal millennial reign at some point in the far future, although opinion on this was divided, and Jerome refers to it as the “millennial fable” in his Commentary on Daniel, as he interprets the Church inheriting an eternal, spiritual kingdom – not an earthly one, along with Eusebius also considering such things as “figurative passages” when speaking against Papias’ literal understanding of it.

There is, though, an extant extra-biblical saying of Jesus which Papias recorded, in which there is a description of life during this millennial reign:

“The Lord used to teach about those times and say: The days will come when vines will grow, each having ten thousand shoots, and on each shoot ten thousand branches, and on each branch ten thousand twigs, and on each twig ten thousand clusters, and in each cluster ten thousand grapes, and each grape when crushed will yield twenty-five measures of wine. And when one of the saints takes hold of a cluster, another cluster will cry out, I am better, take me, bless the Lord through me. Similarly a grain of wheat will produce ten thousand heads, and every head will have ten thousand grains, and every grain ten pounds of fine flour, white and clean. And the other fruits, seeds, and grass will produce in similar proportions, and all the animals feeding on these fruits produced by the soil will in turn become peaceful and harmonious toward one another, and fully subject to humankind.… These things are believable to those who believe. And when Judas the traitor did not believe and asked, How, then, will such growth be accomplished by the Lord?, the Lord said, Those who live until those times will see.”

As we saw in the previous part of this series, some of the earliest writings put the New Jerusalem and Church as being one and the same, coupled with us being the temple where God now dwells to live amongst his people, therefore leaving no room for a future, physical temple to be rebuilt.

Nero fits the 666 and even the “typo” copyist error of 616 (or the Latin variant of Nero’s name), which happened early on, as Irenaeus mentions it around 180 AD.

While there was always an Emperor cult, beginning with Julius Caesar, which made the rulers act as though they had some divinity, Nero properly considered himself divine and Domitian decreed himself “lord and god” and had that printed on all the money. This is often what is thought to be meant by the “mark of the beast” which enables “buying and selling” (Rev 13:17). The Jews had special money minted because of this.

Much of the early church saw the millennium as literal, except some who interpreted it as metaphorical to symbolise completion or totality of God (eg. Like the psalms saying ‘God owns the cattle on 1000 hills’). The general interpretation is that God made the world in 6 days, and since 1 day is as 1000 years with God (2 Peter 3:8), it is fitting that creation lasts that long before Jesus comes back for the eternal Sabbath day. I’m not entirely sure where they got the idea from that Creation should only last that long, but there you go.

If this is accurate, though, and runs according to the Jewish calendar (which counts from day one of creation), then we only have around another 224 years to go before we find out for sure, as we are now in the 5776th year – so that’ll be the year 2239 the world potentially ends, for anyone keeping track!

For a more detailed look at the resurrection and the New Jerusalem, I will do some short follow up articles on those, rather than make this one any longer (Edit: New Jerusalem article is here).

To Conclude

Whichever way you slice it, Revelation seems to be predominantly about the persecutions that the Roman Empire did do, and would continue to do, against the first century Church and beyond (even if there are future applications after the Roman Empire), and that the believers who have to suffer through these times shouldn’t lose faith or hope in God.

But as shown in this article, there are a variety of interpretations and evidences showing various details of Revelation in accord with human history which leads me to caution anyone (myself included) about being overtly dogmatic on any aspect or doctrine derived from Revelation. Even back in Irenaeus’ day (around 180), he wrote in length cautioning believers from getting too caught up in trying to understand the number of the beast and all that it means! You can read more about word/numbers and Irenaeus’ caution here and here respectively.

One of the main themes of Revelation, is that of God’s abode; specifically, his throne. In Rev 4 it is located in Heaven, whereas later in Rev 21, God’s throne is now on Earth in the New Jerusalem where he dwells with his people. The thrust of the book is about holding fast to the Faith, trusting in God when all seems lost, because ultimately, he is coming down to dwell with his people where he will comfort them, bring joy and wipe away every tear (Reclaiming the Book of Revelation, W. E. Glabach, p.28).

This is what it should mean for us today: hope in our God, not a reference guide to the end of the world matched against various news headlines and current events (all of which have undoubtedly failed).

Or to put it more bluntly, in the words of Augustine, who began to view eschatological things as referring to the struggle between good and evil in people:

"Obviously, then it is a waste of effort for us to attempt counting the precise number of years which this world has yet to go, since we know from the mouth of Truth that it is none of our business."

— Augustine of Hippo, City of God, 18:53

Trust God, abide in his love and know that ultimately, He is in control.

Further Reading:

- Reclaiming the Book of Revelation, W. E. Glabach; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7EiliuMmUiYC&pg=PA36&dq=dating+of+the+book+of+revelation&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj61YO6pMnJAhUILhoKHfVCBUsQ6AEIPjAD#v=onepage&q=dating%20of%20the%20book%20of%20revelation&f=false

- Muratorian Canon [ANF 5:603] - http://biblefacts.org/church/MCF.pdf

- C. E. Hill, “The Debate Over the Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon,” Westminster Theological Journal 57:2 (Fall 1995): pp.437-452 http://earlychurch.org.uk/pdf/fragment_hill.pdf

- Young's Concise Critical Bible Commentary, Baker Book House, March 1977, ISBN: 0-8010-9914-5, pg 178.

- http://www.christian-history.org/muratorian-canon.html

- http://web.archive.org/web/20130208060911/http://www.endtimesmadness.com/DatingRev.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk%3ABook_of_Revelation#Nero_banishes_John_to_Patmos_in_Syriac_version.3F

- http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/irenaeus-book5.html

- “The later accounts of John” - http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08492a.htm

- Patmos in the Reception History of the Apocalypse, By Ian Boxall, p.31; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vMRoAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA32&lpg=PA32&dq=clement+tyrant&source=bl&ots=prWq0W9w9B&sig=Vazahpn7o7V1OtPFRTwpUjQWr1I&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj9ufzrns3JAhVFPQ8KHRbDBzQQ6AEIHjAA#v=onepage&q=clement%20tyrant&f=false

- http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/high-holy-days-2014/.premium-1.617185

- https://www.probe.org/four-views-of-revelation/

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250103.htm

- http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/tertullian08.html

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/augustus.shtml

- http://www.religionfacts.com/persecution-of-early-church

- http://historycycles.org/revelation1.html#ref_ednback57

- http://www.pbs.org/empires/romans/empire/titus_domitian.html

- https://www.christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/persecution-in-early-church-gallery

- https://bible.org/question/rome-beast-antichrist-book-revelation

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Roman_emperors

- http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/tac/a15040.htm

- http://www.scripturerevealed.com/prophecy/the-book-of-revelation-an-introduction/

- http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/ancient-rome/the-fall-of-ancient-rome/

- https://www.ccel.org/bible/phillips/CPn27Revelation.htm

- http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/revelation.html

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0125.htm

- http://www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/2013/09/papias-and-the-ten-thousand-branches/

- http://www.agapebiblestudy.com/charts/gemetria%20and%20the%20number%20of%20the%20beast%20666.htm

- http://jdavidstark.com/2011/12/13/irenaeus-on-666-and-616/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130730080621/http://www.lessonsonline.info/MillennialismEarly.htm

Leave a comment Like Back to Top Seen 2.5K times Liked 1 times

Enjoying this content?

Support my work by becoming a patron on Patreon!

By joining, you help fund the time, research, and effort that goes into creating this content — and you’ll also get access to exclusive perks and updates.

Even a small amount per month makes a real difference. Thank you for your support!

Subscribe to Updates

If you enjoyed this, why not subscribe to free email updates and join over 864 subscribers today!

My new book is out now! Order today wherever you get books

Recent Posts

Luke J. Wilson | 19th August 2025 | Fact-Checking

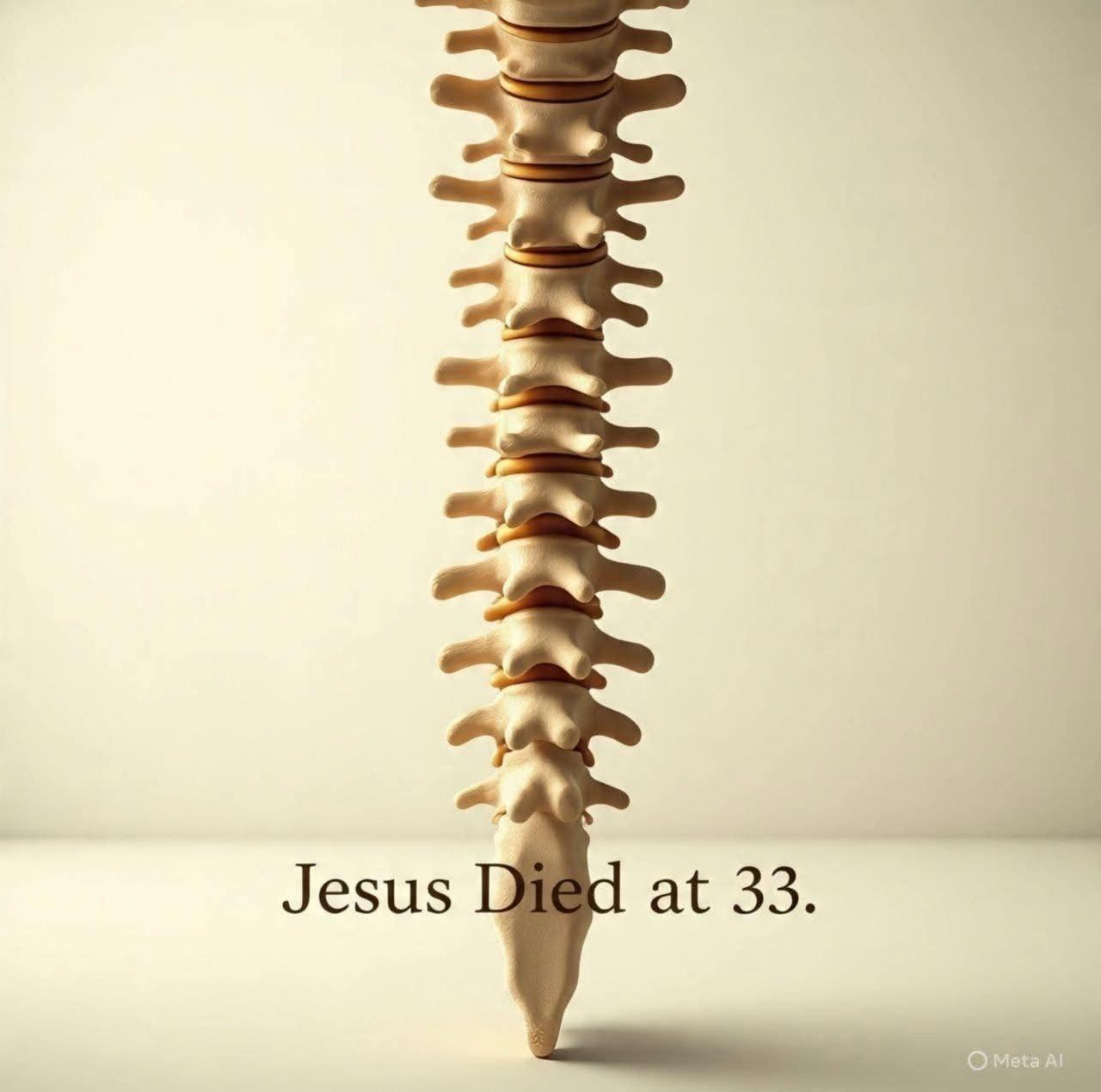

A poetic post has been circulating widely on Facebook, suggesting that our anatomy mirrors various aspects of Scripture. On the surface it sounds inspiring, but when we take time to weigh its claims, two main problems emerge. The viral post circulating on Facebook [Source] First, some of its imagery unintentionally undermines the pre-existence of Christ, as if Jesus only “held the earth together” for the 33 years of His earthly life. Second, it risks reducing the resurrection to something like biological regeneration, as if Jesus simply restarted after three days, instead of being raised in the miraculous power of God. Alongside these theological dangers, many of the scientific claims are overstated or symbolic rather than factual. Let’s go through them one by one. 1. “Jesus died at 33. The human spine has 33 vertebrae. The same structure that holds us up is the same number of years He held this Earth.” The human spine does generally have 33 vertebrae, but that number includes fused bones (the sacrum and coccyx), and not everyone has the same count. Some people have 32 or 34. More importantly, the Bible never says Jesus was exactly 33 when He died — Luke tells us He began His ministry at “about thirty” (Luke 3:23), and we know His public ministry lasted a few years, but His precise age at death is a tradition, not a biblical statement. See my other recent article examining the age of Jesus here. Theologically, the phrase “the same number of years He held this Earth” is problematic. Jesus did not hold the world together only for 33 years. The eternal Word was with God in the beginning (John 1:1–3), and “in Him all things hold together” (Colossians 1:17). Hebrews says He “sustains all things by His powerful word” (Hebrews 1:3). He has always upheld creation, before His incarnation, during His earthly ministry, and after His resurrection. To imply otherwise is to risk undermining the pre-existence of Christ. 2. “We have 12 ribs on each side. 12 disciples. 12 tribes of Israel. God built His design into our bones.” Most people do have 12 pairs of ribs, though some are born with an extra rib, or fewer. The number 12 is certainly biblical: the 12 tribes of Israel (Genesis 49), the 12 apostles (Matthew 10:1–4), and the 12 gates and foundations of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21). But there’s no biblical connection between rib count and these symbolic twelves. This is a case of poetic association, not design woven into our bones. The only real mention of ribs in Scripture is when Eve is created from one of Adam’s ribs in Genesis 2:21–22, which has often led to the teaching in some churches that men have one less rib than women (contradicting this new claim)! 3. “The vagus nerve runs from your brain to your heart and gut. It calms storms inside the body. It looks just like a cross.” The vagus nerve is real and remarkable. It regulates heart rate, digestion, and helps calm stress, and doctors are even using vagus nerve stimulation as therapy for epilepsy, depression, and inflammation showing it really does “calm storms” in the body. But it does not look like a cross anatomically. The language about “calming storms” may echo the way Jesus calmed the storm on the Sea of Galilee (Mark 4:39), but here again the poetic flourish stretches science (and Scripture) beyond what’s accurate. 4. “Jesus rose on the third day. Science tells us that when you fast for 3 days, your body starts regenerating. Old cells die. New ones are born. Healing begins. Your body literally resurrects itself.” There’s a serious theological problem here. To equate Jesus’ resurrection with a biological “regeneration” after fasting is to misrepresent what actually happened. Fasting can indeed trigger cell renewal and immune repair, but it cannot bring the dead back to life. It’s still a natural process that happens...

Luke J. Wilson | 08th July 2025 | Islam

“We all worship the same God”. Table of Contents 1) Where YHWH and Allah Appear Similar 2) Where Allah’s Character Contradicts YHWH’s Goodness 3) Where Their Revelations Directly Contradict Each Other 4) YHWH’s Love for the Nations vs. Allah’s Commands to Subjugate 5) Can God Be Seen? What the Bible and Qur’an Say 6) Salvation by Grace vs. Salvation by Works Conclusion: Same God? Or Different Revelations? You’ve heard it from politicians, celebrities, and even some pastors. It’s become something of a modern mantra, trying to shoehorn acceptance of other beliefs and blend all religions into one, especially the Abrahamic ones. But what if the Bible and Qur’an tell different stories? Let’s see what their own words reveal so you can judge for yourself. This Tweet recently caused a stir on social media 1) Where YHWH and Allah Appear Similar Many point out that Jews, Christians, and Muslims share a belief in one eternal Creator God. That’s true — up to a point. Both the Bible and Qur’an describe God as powerful, all-knowing, merciful, and more. Here’s a list comparing some of the common shared attributes between YHWH and Allah, with direct citations from both Scriptures: 26 Shared Attributes of YHWH and Allah According to the Bible (NRSV) and the Qur’an Eternal YHWH: “From everlasting to everlasting you are God.” — Psalm 90:2 Allah: “He is the First and the Last…” — Surah 57:3 Creator YHWH: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” — Genesis 1:1 Allah: “The Originator of the heavens and the earth…” — Surah 2:117 Omnipotent (All-Powerful) YHWH: “Nothing is too hard for you.” — Jeremiah 32:17 Allah: “Allah is over all things competent.” — Surah 2:20 Omniscient (All-Knowing) YHWH: “Even before a word is on my tongue, O LORD, you know it.” — Psalm 139:4 Allah: “He knows what is on the land and in the sea…” — Surah 6:59 Omnipresent (Present Everywhere) YHWH: “Where can I go from your Spirit?” — Psalm 139:7–10 Allah: “He is with you wherever you are.” — Surah 57:4 Holy YHWH: “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts.” — Isaiah 6:3 Allah: “The Holy One (Al-Quddus).” — Surah 59:23 Just YHWH: “A God of faithfulness and without injustice.” — Deuteronomy 32:4 Allah: “Is not Allah the most just of judges?” — Surah 95:8 Merciful YHWH: “The LORD, merciful and gracious…” — Exodus 34:6 Allah: “The Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.” — Surah 1:1 Compassionate YHWH: “As a father has compassion on his children…” — Psalm 103:13 Allah: “He is the Forgiving, the Affectionate.” — Surah 85:14 Faithful YHWH: “Great is your faithfulness.” — Lamentations 3:22–23 Allah: “Indeed, the promise of Allah is truth.” — Surah 30:60 Unchanging YHWH: “For I the LORD do not change.” — Malachi 3:6 Allah: “None can change His words.” — Surah 6:115 Sovereign YHWH: “The LORD has established his throne in the heavens…” — Psalm 103:19 Allah: “Blessed is He in whose hand is dominion…” — Surah 67:1 Loving YHWH: “God is love.” — 1 John 4:8 Allah: “Indeed, my Lord is Merciful and Affectionate (Al-Wadud).” — Surah 11:90 Forgiving YHWH: “I will not remember your sins.” — Isaiah 43:25 Allah: “Allah forgives all sins…” — Surah 39:53 Wrathful toward evil YHWH: “The LORD is a jealous and avenging God…” — Nahum 1:2 Allah: “For them is a severe punishment.” — Surah 3:4 One/Unique YHWH: “The LORD is one.” — Deuteronomy 6:4 Allah: “Say: He is Allah, One.” — Surah 112:1 Jealous of worship YHWH: “I the LORD your God am a jealous God.” �...

Luke J. Wilson | 05th June 2025 | Blogging

As we commemorated the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation this year, the familiar image of Martin Luther striding up to the church door in Wittenberg — hammer in hand and fire in his eyes — has once again taken centre stage. It’s a compelling picture, etched into the imagination of many. But as is often the case with historical legends, closer scrutiny tells a far more nuanced and thought-provoking story. The Myth of the Door: Was the Hammer Ever Raised? Cambridge Reformation scholar Richard Rex is one among several historians who have challenged the romanticised narrative. “Strangely,” he observes, “there’s almost no solid evidence that Luther actually went and nailed them to the church door that day, and ample reasons to doubt that he did.” Indeed, the first image of Luther hammering up his 95 Theses doesn’t appear until 1697 — over 180 years after the fact. Eric Metaxas, in his recent biography of Luther, echoes Rex’s scepticism. The earliest confirmed action we can confidently attribute to Luther on 31 October 1517 is not an act of public defiance, but the posting of two private letters to bishops. The famous hammer-blow may never have sounded at all. Conflicting Accounts Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s successor and first biographer, adds another layer of complexity. He claimed Luther “publicly affixed” the Theses to the door of All Saints’ Church, but Melanchthon wasn’t even in Wittenberg at the time. Moreover, Luther himself never mentioned posting the Theses publicly, even when recalling the events years later. Instead, he consistently spoke of writing to the bishops, hoping the matter could be addressed internally. At the time, it was common practice for a university disputation to be announced by posting theses on church doors using printed placards. But no Wittenberg-printed copies of the 95 Theses survive. And while university statutes did require notices to be posted on all church doors in the city, Melanchthon refers only to the Castle Church. It’s plausible Luther may have posted the Theses later, perhaps in mid-November — but even that remains uncertain. What we do know is that the Theses were quickly circulated among Wittenberg’s academic elite and, from there, spread throughout the Holy Roman Empire at a remarkable pace. The Real Spark: Ink, Not Iron If there was a true catalyst for the Reformation, it wasn’t a hammer but a printing press. Luther’s Latin theses were swiftly reproduced as pamphlets in Basel, Leipzig, and Nuremberg. Hundreds of copies were printed before the year’s end, and a German translation soon followed, though it may never have been formally published. Within two weeks, Luther’s arguments were being discussed across Germany. The machinery of mass communication — still in its relative infancy — played a pivotal role in what became a theological, political, and social upheaval. The Letters of a Conscientious Pastor Far from the bold revolutionary of popular imagination, Luther appears in 1517 as a pastor deeply troubled by the abuse of indulgences, writing with respectful concern to those in authority. In his letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, he humbly addresses the archbishop as “Most Illustrious Prince,” and refers to himself as “the dregs of humanity.” “I, the dregs of humanity, have so much boldness that I have dared to think of a letter to the height of your Sublimity,” he writes — hardly the voice of a man trying to pick a fight. From Whisper to Roar Luther’s initial appeal through formal channels was, predictably, ignored. He was advised not to make trouble. But as opposition mounted and corruption remained unchecked, the once quiet reformer grew louder. His theological convictions deepened, and his public persona evolved. The lion did eventually roar — but not on October 31. A Catholic Reformer, Not a Protestant Founder It’s vital to remem...

Luke J. Wilson | 20th May 2025 | Islam

You are not alone. Around the world, many Muslims — people who already believe in one God, pray, and seek to live righteously — are drawn to know more about Jesus (ʿĪsā in Arabic). Some have heard He is more than a prophet. Some have sensed His presence in a dream or vision. And some simply long to know God more deeply, personally, and truly. So what does it mean to become a Christian? And how can you take that step? This guide is for you. 1. What Christians Believe About God and Jesus ➤ One God, Eternal and Good Christians believe in one God — the same Creator known to Abraham, Moses, and the prophets. But we also believe God is more personal and relational than many realise. In His love, He has revealed Himself as Father, Son (Jesus), and Holy Spirit — not three gods, but one God in three persons. ➤ Jesus Is More Than a Prophet Muslims honour Jesus as a great prophet, born of the virgin Mary. Christians also affirm this — but go further. The Bible teaches that Jesus is the Word of God (Kalimat Allāh), who became flesh to live among us. He performed miracles, healed the sick, raised the dead — and lived without sin.Jesus came not just to teach but to save — to bring us back to God by bearing our sins and rising again in victory over death. 2. Why Do We Need Saving? ➤ The Problem: Sin All people — no matter their religion — struggle with sin. We lie, get angry, feel jealous, act selfishly, or fail to love God fully. The Bible says: “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” (Romans 3:23) Sin separates us from God. And no matter how many good deeds we do, we can never make ourselves perfect or holy before Him. ➤ The Solution: Jesus Because God loves us, He did not leave us in our sin. He sent Jesus, His eternal Word, to live as one of us. Jesus died willingly, offering His life as a sacrifice for our sins, then rose again on the third day. “But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us.” (Romans 5:8) 3. How Do I Become a Christian? Becoming a Christian is not about joining a Western religion. It’s about entering a relationship with God through faith in Jesus Christ. Here is what the Bible says: ✝️ 1. Believe in Jesus Believe that Jesus is the Son of God, that He died for your sins, and that He rose again. “If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” (Romans 10:9) 💔 2. Repent of Your Sins Turn away from sin and ask God to forgive you. This is called repentance. It means being truly sorry and choosing a new way. “Repent therefore, and turn to God so that your sins may be wiped out.” (Acts 3:19) 💧 3. Be Baptised Jesus commands His followers to be baptised in water as a sign of their new life. Baptism represents washing away your old life and rising into a new one with Jesus. “Repent and be baptised every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven.” (Acts 2:38) 🕊️ 4. Receive the Holy Spirit When you believe in Jesus, God gives you the Holy Spirit to live within you, guiding you, comforting you, and helping you follow His will. “You received the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Romans 8:15) 🧎 5. Begin a New Life As a Christian, you are born again — spiritually renewed. You begin to grow in faith, love, and holiness. You read the Bible, pray, fast, and gather with other believers. Your life is no longer your own; you now live for God. 4. What Does a Christian Life Look Like? Jesus said: “If anyone wants to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” (Matthew 16:24) This means: Loving God with all your heart Loving your neighbour — even your enemies Forgiving others ...