Melchizedek to Jesus: The Divine Thread of Bread and Wine

This past Sunday at church, we were looking at Genesis 14 in the sermon. There’s a lot going on in this chapter with nine different kings all at war fighting one another, and Abram and Lot somehow mixed up in the middle of it (this is before Abram is renamed to Abraham). Sodom gets invaded, Lot gets taken captive (along with everyone else) and then Abram mounts a daring rescue with 318 of his men! It’s really quite action-packed for such a short chapter. I don’t know about you, but I always think of Abraham as this kindly old man, not some tribal warrior ready to go all “Taken” on his enemies (Gen 14:14–16).

It’s in the midst of all this action that we meet a mysterious character who pretty much just turns up out of nowhere: Melchizedek, king of Salem.

He is one of those characters from the Old Testament whose actions reverberate down through history into the New Testament era and beyond and into our present-day worship. Despite the number of kings fighting all across Canaan, Melchizedek doesn’t appear to be a part of these conflicts and only enters the scene when it’s all over, and Abram has rescued Lot and subdued the king who captured Sodom. Then “the king of Sodom went out to meet [Abram] at the Valley of Shaveh, that is, the King’s Valley.” (Gen 14:17), which is modern-day Kidron Valley, just outside of Jerusalem. So the meeting was local and close to Melchizedek, but still doesn’t explain what happens next to Abram:

Genesis 14:18–20

And King Melchizedek of Salem brought out bread and wine; he was priest of God Most High. He blessed him and said,

“Blessed be Abram by God Most High,

maker of heaven and earth,

and blessed be God Most High,

who has delivered your enemies into your hand!”

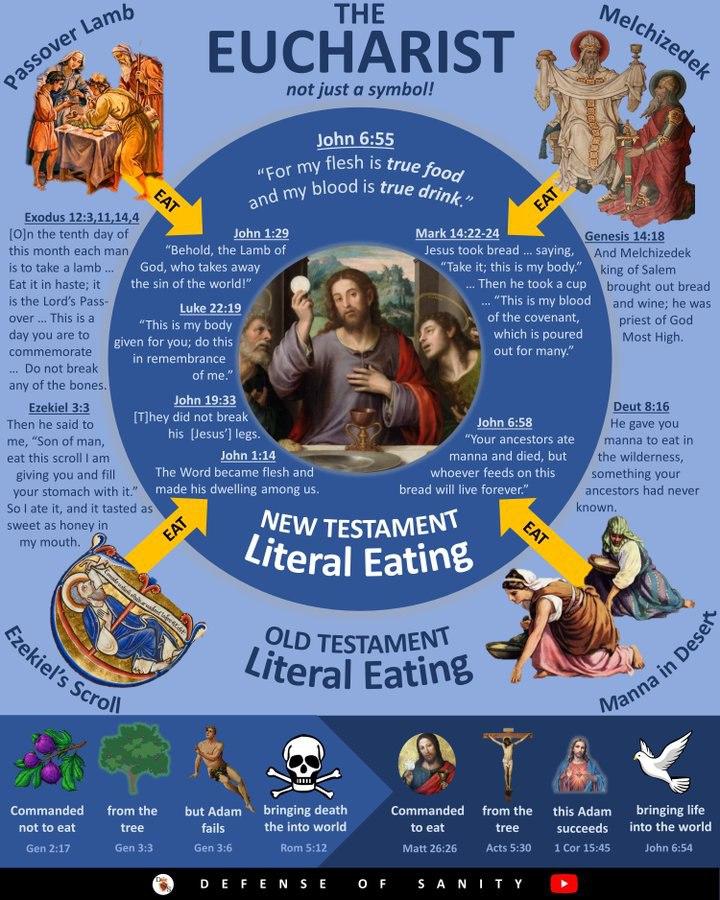

The blessing of bread and wine by Melchizedek connects us with the divine thread that will flow through all time and history: the then-future Passover and, ultimately, with Jesus’ institution of the Eucharist. This connection underscores a sacred continuity that we, as Christians, continue to partake in today until Jesus returns.

Melchizedek: Priest and King

Melchizedek appears in Genesis 14:18–20, where he is described as the king of Salem and a priest of the Most High God. His encounter with Abram (Abraham) is brief but significant. He brings out bread and wine and blesses Abraham. He then responds by giving Melchizedek a tenth of everything. Both of these acts point to aspects of the Law, tithes and sacrifices, which at this point in time had not yet been given, which leaves us with more unanswered questions regarding what this priesthood of Melchizedek was (and its origins), and also why Abraham would give a tenth like a tithe.

Salem, which is understood to be the ancient name for Jerusalem, means “city of peace”. This is highly significant as it links to the messianic prophecy of Jesus being the Prince of Peace (Isaiah 9:6). The connection between Melchizedek being the king of Salem and Jesus being in the lineage of David, who reigned in Jerusalem, ties the notion of peace directly into the divine narrative. Melchizedek’s role as a king and priest in the city of peace prefigures the ultimate role of Jesus as Messiah.

Jesus, the Prince of Peace, not only fulfils the royal lineage through King David but also the priestly order of Melchizedek. Hebrews 7:2–3 elaborates on Melchizedek’s name and title, explaining that Melchizedek “means ‘king of righteousness’; next, he is also king of Salem, that is, ‘king of peace’.” This dual kingship of righteousness and peace perfectly summarises Jesus’ ministry and mission.

Psalm 110:4 further cements Melchizedek’s significance by declaring the Messiah as “a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek”. This eternal priesthood signifies a lasting peace and righteousness that Jesus embodies and imparts to His followers (John 14:27). Thus, Melchizedek’s brief appearance becomes a profound foreshadowing of Christ’s eternal kingship and priesthood.

The Passover: A Foreshadowing

Fast forward to the Exodus, and we encounter another crucial element: the Passover. This event marks the Israelites’ deliverance from Egyptian bondage, involving the sacrifice of a spotless lamb and the eating of unleavened bread and bitter herbs. God commanded that this meal be observed annually as a lasting ordinance (Exodus 12:14). The blood of the lamb, smeared on the doorposts, protected the Israelites from the plague of the firstborn.

The Passover meal, with its elements of bread and wine, pointed forward to a greater deliverance. It wasn’t just a historical commemoration but a foreshadowing of the ultimate Passover lamb, Jesus Christ, whose sacrifice would bring deliverance from the bondage of sin. The elements of the meal — bread and wine — are steeped in symbolism and divine foreshadowing.

The Institution of the Eucharist

During the Last Supper, Jesus transformed the Passover meal into something new and everlasting.

Luke 22:19–20

Then he took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” And he did the same with the cup after supper, saying, “This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood”.

In this moment, Jesus fulfilled and transcended the Passover. The bread and wine of Melchizedek’s blessing, and the elements of the Passover meal, found their ultimate meaning in the Eucharist. Jesus established a new covenant, one that was sealed with His own blood, not the blood of lambs. His body and blood, present in the bread and wine, became the means by which His followers would continue to partake in His sacrifice and receive His grace.

This transformative act of Jesus is highlighted further in John 6, where He delivers His Bread of Life discourse. Jesus declares, “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever, and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh” (John 6:51). He continues, “Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day” (John 6:54). These statements caused confusion and controversy among His listeners, yet they hint towards the spiritual reality of the Eucharist as a true participation in the body and blood of Christ and affirm the belief that the Eucharist is not merely symbolic, but a real and mysterious participation in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This is also something that was recognised by a number of Early Church Fathers in their commentary and interpretations of John 6.

The Eucharist Today

The Eucharist (from the Greek meaning “thanksgiving”), also known as Holy Communion or the Lord’s Supper, is central to Christian worship, or at least, it should be. In partaking of the bread and wine, Christians around the world and throughout history join in a spiritual mystery. As Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 10:16–17, “The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.”

In every Communion service, we are not merely remembering a past event but participating in the ongoing reality of Christ’s sacrificial love. The Eucharist is a means of grace, a tangible encounter with the divine. It unites us with Christ and with each other, as we become one body through this sacred and sacramental meal. Paul explains this mystery further by contrasting with the people of Israel, and how they become “partners in the altar” (v.18) when they eat of the sacrifices, and also how those gentiles who sacrifice to idols become “partners with demons” (v.20). This is to say that it is more than mere symbolism going on when we celebrate the Lord’s Supper, and partaking in an unworthy manner can mean you are profaning the body and blood of Christ, and is the reason some people are sick and have died (1 Corinthians 11:27–31)!

This understanding has been carried through the history of the Church, from early writers such as Ignatuis (c.110) writing against the docetic heresy, who said, “they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ” (Smyrnaeans, VII) and he even calls it the “medicine of immortality” in his letter to the Ephesians; to Justin Martyr (c.150) who explained that is it not received as “common bread and common drink” and that “our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished” (First Apology, LXVI).

Jerome also recognises a connection with Melchizedek, when he says, “After the type had been fulfilled by the Passover celebration and He had eaten the flesh of the lamb with His Apostles, He takes bread which strengthens the heart of man, and goes on to the true Sacrament of the Passover, so that just as Melchisedech, the priest of the Most High God, in prefiguring Him, made bread and wine an offering, He too makes Himself manifest in the reality of His own Body and Blood” (Jerome, Commentaries on the Gospel of Matthew, c.398). And in 490, Gelasius, Bishop of Rome wrote: “By the sacraments we are made partakers of the divine nature, and yet the substance and nature of bread and wine do not cease to be in them” (Adversus Eutychen et Nestorium, 14). I could go on and on with this, as it’s one of the doctrines from the early church which finds near total unanimity in those who wrote about it (and there were many!), and that in itself should cause us to stop and consider the importance here if the teaching was consistent for 1800+ years.

Conclusion

The connection from Melchizedek’s blessing of bread and wine, through the Passover, to Jesus’ institution of the Eucharist, forms a sacred continuity that enriches our faith and worship. Melchizedek’s seemingly isolated action prefigured the blessing in the Passover, which in turn was a foreshadowing of Christ’s sacrifice and the Last Supper which established the Eucharist.

As Christians, every time we partake in the Eucharist, we are joining in a divine mystery that spans millennia, connecting us with the faithful of the past, present, and future. We remember and proclaim the Lord’s death until He comes, and through this holy sacrament, we receive His life-giving grace. This powerful connection not only anchors our faith but also propels us into the world as bearers of His love and peace, established by His power and filled with the Holy Spirit!

Further Reading

- How was Jesus a sacrifice? | The Sacred Faith: Timeless Truths for Modern Minds

- What is the significance of the four cups of wine? — Chabad.org

- Docetism | Theopedia

- Ignatius of Antioch: Letter to the Smyrnaeans | Patristics.info

- Ignatius of Antioch: Letter to the Ephesians | Patristics.info

- Justin Martyr: First Apology | Patristics.info

- Early Church Fathers Upholding Transubstantiation in Their Own Words — Ascension Press Media

- Early Church Fathers on the Real Presence in the Eucharist | Bread. (breadtobody.com)

- The Real Presence — Church Fathers

- Fathers of the Church on the Eucharist (therealpresence.org)

- The Eucharist and John 6: A Former Protestant's Perspective - Clarifying Catholicism

- Two-Edged Sword: The Eucharist, John 6, and the early church (twoedgedsword.blogspot.com)

Leave a comment Like Back to Top Seen 1.4K times Liked 0 times

Enjoying this? Consider contributing regular gifts for this content on Patreon.

* Patreon is a way to join your favorite creator's community and pay them for making the stuff you love. You can simply pay a few pounds per month or per post that a creator makes, and in return receive some perks!

Subscribe to Updates

If you enjoyed this, why not subscribe to free email updates and join over 842 subscribers today!

My new book is out now! Order today wherever you get books

Recent Posts

Luke J. Wilson | 5 days ago | Easter

Over the years, I’ve encountered many Christians who’ve quoted from Alexander Hislop’s The Two Babylons as if it were a solid historical resource. The book claims that the Roman Catholic Church is not truly Christian but rather a continuation of ancient Babylonian religion. It’s self-assured and sweeping, and for many people, it seems to explain everything, from Marian devotion to Lent and Easter, to Christmas, as rooted in paganism. But is it accurate? In short: no, it really isn’t. Hislop’s work is a classic example of 19th-century pseudohistory — a polemical piece, written to prove a point, not to explore any historical truth. Flawed Methods and Wild Claims Hislop argues that most Catholic practices — from the Mass and clerical robes to festivals like Christmas and Easter — were somehow borrowed from Babylonian religion. The problem being that Hislop doesn’t rely on primary sources or credible historical data. Instead, he draws connections based on word similarities (like Easter and Ishtar) or visual resemblances (like Mary and child compared with mother-goddess statues from ancient cultures). But phonetic resemblance isn’t evidence, and neither is visual similarity. For example, if I say “sun” and “son” in English, they may sound alike, but they aren’t the same thing. That’s the level of reasoning at work in much of The Two Babylons. Hislop often lumps together completely different ancient figures — Isis, Semiramis, Ishtar, Aphrodite — as if they were all just variations of the same deity. He then tries to say Mary is just the Christian version of this pagan goddess figure. But there’s no credible evidence for that at all. Mary is understood through the lens of Scripture and Christian theology, not through pagan myth. The earliest depictions of Mary and the Christ-child date back to the second century and do not resemble any of the pagan idols. But, again, the common accusations are based on superficial similarities of a woman nursing a child. That’s going to look the same no matter who or what does that! Oldest depiction of Mary. Dura-Europos Church, Syria, 2nd century What About Lent and Tammuz? One of Hislop’s more popular claims is that Lent comes from a Babylonian mourning ritual for the god Tammuz, mentioned in Ezekiel 8:14. He argues that early Christians borrowed the 40-day mourning period and just rebranded it. But this doesn’t line up with the evidence. Lent developed as a time of fasting and repentance leading up to Easter — especially for new believers preparing for baptism. The number forty comes from Scripture: Jesus’ forty days in the wilderness, Moses’ fast on Sinai, and Elijah’s journey to Horeb. Church Fathers like Irenaeus and Athanasius saw it as a time for self-denial and spiritual renewal — not mourning a pagan god. Yes, there are pagan festivals that involve seasonal death and rebirth stories. But similarity does not mean origin. If that logic held, then even Jesus’ resurrection would be suspect because pagan cultures also told resurrection-like stories. Yet the gospel stands apart — not because of myth but because of history and revelation. Why Hislop’s Work Persists Even though The Two Babylons is poor scholarship, it’s unfortunately had a long shelf life. That’s partly because it appeals to a certain kind of suspicion. If you’re already sceptical about the Catholic Church, Hislop offers an easy explanation: “It’s all pagan!”. But history isn’t ever that simple. And theology — especially the theology handed down through the ages by the faithful— isn’t built on conspiracy and apparent obscure connections, but on Christ and the truth of the Scriptures. Interestingly, even Ralph Woodrow, a minister who once wrote a book defending Hislop’s ideas, later retracted his views after digging deeper into the evidence. He eventually wrote a book called The Babylon Connect...

Darwin to Jesus | 16th April 2025 | Atheism

Guest post by Darwin to Jesus Dostoevsky famously said, “If there is no God, then everything is permitted.” For years, as an atheist, I couldn’t understand what he meant, but now I do… Here’s a simple analogy that shows why only theism can make sense of morality: Imagine you just got hired at a company. You show up, set up your desk, and decide to use two large monitors. No big deal, right? But then some random guy walks up to you and says: “Hey, you’re not allowed to do that.” You ask, “What do you mean?” They say, “You’re not permitted* to use monitors that big.” In this situation, the correct response would be: “Says who?” We’ll now explore the different kinds of answers you might hear — each one representing a popular moral theory without God — and why none of them actually work. Subjective Morality The random guy says, “Well, I personally just happen to not like big monitors. I find them annoying.” Notice that’s not a reason for you to change your setup. Their personal preferences don’t impose obligations on you. This is what subjective morality looks like. It reduces morality to private taste. If this were the answer, you’d be correct to ignore this person and get back to work — big monitors are still permitted. Cultural Relativism Instead, they say, “It’s not just me — most people here don’t use big monitors. It’s not our culture.” That’s cultural relativism: right and wrong are just social customs, what is normal behavior. But notice customs aren’t obligations. If the culture were different, the moral rule would be different, which means it isn’t really moral at all. You might not fit in. You might not be liked. But you’re still permitted to use big monitors. Emotivism Here after being asked “says who?” the person just blurts out, “Boo, big monitors!” You reply, “Hurrah, big monitors!” That’s the entire conversation. This is emotivism. On this moral theory when we talk about right and wrong we’re actually just expressing our personal feelings towards actions, I boo rape, you hurrah rape. But shouting “boo!” at someone doesn’t create real obligations. You’re still permitted to use large monitors. Utilitarianism Here, the person says, “Your big monitors lower the overall productivity of the office. You’re not permitted to use them because they lead to worse consequences.” This is utilitarianism: morality is based on producing the greatest happiness for the greatest number. But even if that’s true — so what? Who says you’re obligated to maximize group productivity? And what if your monitors actually help you work better? Utilitarianism might tell you what leads to better outcomes, but it doesn’t tell you why you’re morally obligated to follow that path — especially if it comes at your own expense. You’re still permitted to use large monitors. Virtue Ethics Here they say, “Using big monitors just doesn’t reflect the virtues we admire here — simplicity, humility, restraint.” This is virtue ethics. Morality is about becoming the right kind of person. But who defines those virtues? And why are you obligated to follow them? What if your idea of a virtuous worker includes productivity and confidence? Without a transcendent standard, virtues are just cultural preferences dressed up in moral language. If you don’t care about virtue or their arbitrary standards, then you have no obligation. You’re still permitted to use large monitors. Atheist Moral Realism But what if they say, “Listen, there’s a rule. It’s always been here. It says you can’t use monitors that large.” You ask, “Who made the rule?” They say, “No one.” You ask, “Who owns this company?” They say, “No one owns it. The company just exists.” You look around and ask, “Where is the rule?” They say, “You won’t find it w...

Luke J. Wilson | 09th April 2025 | History

We often hear that Jesus was “about 33 years old” when he was crucified and only had a three-year ministry. But have you ever wondered how precise that number is, or why we assume that was his age, especially when Scripture doesn’t specify? Table of Contents The Gospel of Luke: “About Thirty” Early Church Testimony: Irenaeus and the Longer Ministry Historical Anchors: Birth, Pilate, and the Crucifixion Window The Death of Herod Cross-referencing with Pilate, Caiaphas, and Jesus When Did Tiberius Begin to Reign? 1. From his co-regency with Augustus (AD 11–12) 2. From the death of Augustus (AD 14) How Does This Affect Jesus’ Age and Ministry Start? Astronomy and the Timing of Passover Estimated Lengths of Jesus’ Ministry Why This Matters In Summary Further Reading I’ve long wondered about this, especially when the Pharisees accused Jesus of not being close to fifty, which seems odd if he was only in his early 30s. Then I later discovered Irenaeus also had similar thoughts in the second century, and the plot thickened! I’ve had this rumbling around in the back of my mind for a few years now and slowly chewed it over. So now I’m going to try and present the evidence, rather than rely solely on tradition and assumptions, and piece together what the Gospels, early Church Fathers, historical data, and even astronomy can tell us about the potential age of Jesus and the length of his ministry. What follows is a deeper, richer look at the life and death of Jesus and what we can learn by following the evidence. The Gospel of Luke: “About Thirty” Luke 3:23 tells us plainly: Jesus was about thirty years old when he began his work. This statement has historically been the anchor point for dating Jesus’ ministry. Most take this to mean he was around 30 at his baptism, which marked the beginning of his public ministry. Something to bear in mind here is that Luke isn’t exact and only says “about thirty”, so he could have been slightly younger or older at the time. But being around the age of 30 would align with the requirements of priests, which Jesus was also fulfilling the role of (Hebrews 2:17; Numbers 4:1–4; Numbers 8:23–25). But from there, it’s traditionally assumed that Jesus ministered for just three years before his death, mainly based on the Gospel of John, which mentions three Passovers (John 2:13, 6:4, 11:55). However, John also says at the end of his Gospel in John 21:25: But there are also many other things that Jesus did; if every one of them were written down, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written. This is a clear reminder, even if John is being hyperbolic here: not everything was recorded. Considering that the Synoptic Gospels only mention one Passover, the number of Passovers we read about in John may not reflect the total number Jesus experienced during his ministry. They may also serve a theological point (three being a prominent number in Scripture) rather than a chronological one. Early Church Testimony: Irenaeus and the Longer Ministry In the second century, Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon and disciple of Polycarp (who had also known the Apostle John and was likely his disciple), made an interesting claim about the age of Jesus — and backed it up by saying it was verified by the Apostle John himself! In Against Heresies (2.22.4–6), Irenaeus wrote: …our Lord possessed [old age] while He still fulfilled the office of a Teacher, even as the Gospel and all the elders testify, those who were conversant in Asia with John, the disciple of the Lord, [affirming] that John conveyed to them that information. … Some of them, moreover, saw not only John but the other apostles also, and heard the same account from them, and bear testimony to this statement. He argued that the line in John 8:57: Then the Jews said to him, ‘You are not yet fifty years old, and have you seen Abraha...

KingsServant | 12th March 2025 | Islam

This is a guest post by “KingsServant” In 2019 a book called Defying Jihad was published by Tyndale House, the reputable Christian publisher telling the story of “Esther Ahmad” a pseudonym used by the author alongside her co-author Craig Borlase, who has previously written alongside, well known Christian personalities such as Matt Redman the singer and Andrew Brunson, an American pastor imprisoned by the Turkish government. As I began to read this book over this past year I was expecting an encouraging account of how a former Jihadi found Christ and escaped her previous accomplices. Very quickly, however, I became uncomfortable, her descriptions of her background involved allegedly committed Muslims doing very un-Islamic things and the unnamed militant group doing unusual things that didn’t fit my knowledge gained from years of study of Islam and interactions with Muslims, including extremists. As my doubts about the authenticity of the book solidified, and yet I couldn’t find anyone else who had questioned these things before me, or on the other hand provided verification of her story. I decided to contact Craig. During our brief and cordial email exchange he told me that he had been in touch with people who knew Esther after she escaped her family home, but so far has not suggested he has any other lines of evidence confirming any of the key elements of her account before that time. As a result, I am writing this article to draw attention to the aspects that raise suspicion. According to “Esther’s” story, she was raised in Pakistan where she was sent to an extremist madrassa (or Muslim school) for girls, there they were shown images of victims of violence and told that Christians and Jews were responsible - the emphasis on Jews and particularly Christians by a militant group based in Pakistan is strange. All the terrorist groups in Pakistan direct their efforts towards Hindus (especially in Kashmir) or other Muslims, since Christians are such a tiny minority there. Things rapidly become even stranger when a Mullah displays weapons to the group of girls telling them “… one day you will get to handle these” as the book continues describing them being encouraged to aspire to physical violence towards Jews and Christians specifically, the description of “Aunt Selma” volunteering for and dying fighting Jihad is likewise out of place. Islamic terrorist groups very rarely recruit women for combat roles, as Devorah Margolin describes Hamas and ISIS as departing from convention by encouraging female participation in violence and even then in only a very restricted way under particular circumstances with a specific fatwa (or Islamic ruling) being issued.1 On page 33, the militant group leader “Anwar” suggests that Esther could find a husband in the west to bring him to Islam. It is strictly forbidden for a Muslim woman to marry a non Muslim man, the idea that they would be encouraged by a scholar to date is about as unbelievable. In a conservative Pakistani culture, she would more likely find herself the victim of a so-called “honour killing” for such a thing.2 After her initial chance encounters with her future husband “John” (not as a result of trying to follow “Anwar’s” advice), on page 92 it is recorded that he said to her “… I’m not against your faith and beliefs…”, it’s the kind of thing that we might expect a liberal in the west to say, but not a Pakistani believer who knows that Islam denies that Jesus is the Son of God and that he died for sinners. Following her conversion according to her account, she engaged in a number of public debates with clerics in which she defended her decision to leave Islam and follow Christ. It is not uncommon for apostates to have meetings with scholars arranged by their family members in the hope that they might be won back to Islam, but it is very surprising that her influential father would want to give his apostate daughter su...