Man-Made Tradition vs Apostolic Tradition

Quite often in discussions which are about or involve some aspects of early church history or practices earlier Christians did, someone will inevitably throw out the "show stopper" that is "it's all just man made tradition" therefore not valid and the discussion is over. It’s as though saying it's "man made", without considering anything other than that they can't find an isolated chapter and verse in the bible which states something explicitly, means they've "won" the debate!

Nothing more to see here folks, someone told us it's man made so we can all go home now.

Either that, or the mere mention of the word “tradition” and suddenly you’re accused of being a Roman Catholic or that any Church tradition only has its basis in the Roman Catholic Church, and is therefore automatically wrong and invalid in a discussion, and/or in practice.

Except that's not exactly true nor a good way to discuss anything (and probably falls under the Post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy).

Traditions and creeds go back much further than you might think – all the way back to a time of the Apostles.

Yes, Jesus had a go at all the Pharisees for making their traditions greater than Scripture (Matt 15:2-3; Mark 7:9) and in that case dismissing something as "man made" is valid.

But what about when it's something based on or inspired by Scripture, something that becomes almost 'living exegesis' rather than just head knowledge? I've been thinking of Lent lately, as that often is dismissed as "man made” or “Catholic tradition" without looking at the history or how the practice came to be.

Generally, no one has an issue with you saying that you're going to fast, but say you'll do it at a specific time of year or for a certain length of time, and suddenly it's wrong and “man made”?

What do the Scriptures say?

Colossians 2:8

See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ.

This is often something quoted as a backup to arguing against traditions. Paul’s warnings here are quite valid, we should be careful what we believe and follow as Christians. This is a warning against "man made traditions" but what if I told you that Paul also tells the churches to FOLLOW traditions too?

1 Corinthians 11:2

I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions just as I handed them on to you.

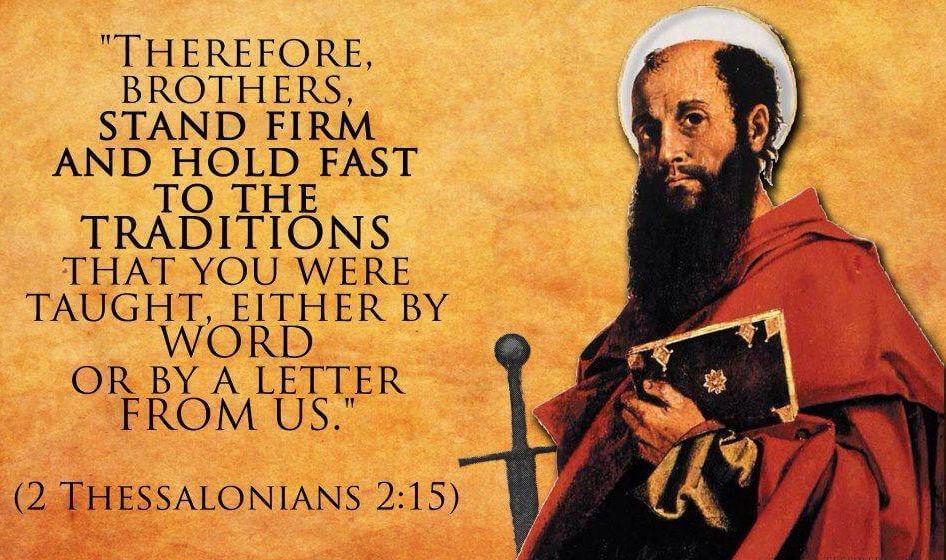

2 Thessalonians 2:15

So then, brothers and sisters, stand firm and hold fast to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by our letter.

2 Thessalonians 3:6

Now we command you, beloved, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, to keep away from believers who are living in idleness and not according to the tradition that they received from us.Philippians 4:9

Keep on doing the things that you have learned and received and heard and seen in me, and the God of peace will be with you.

Did you catch the theme here? "Hold fast to the traditions" that the apostles taught the believers, either “by word”, action, or by letter!

There is a big difference between "man made tradition" and Apostolic tradition. The former meaning heathen or non-Christian beliefs, or those added as extra rules on top of God’s commands, and the latter being things which will help the Church grow together in Christ.

The key word here is “Apostolic”.

We only have a handful of the apostles letters still, which now forms our New Testament, so anything else they taught was done orally and in person to the people they discipled. These were the traditions they handed down to be observed.

How can we know what else they taught?

All's not lost though! Those who followed the apostles wrote down many things which they were taught, so that they could then in turn, teach the churches the "traditions" passed onto them. These early Christians well understood the difference between the “man made traditions” which Jesus warned against, and those of apostolic origin.

Bishop of Carthage, Cyprian, who was a prominent early leader and writer (c. 250 AD), sums up the view on human tradition rather well, when he says:

...what presumption, to prefer human tradition to divine ordinance, and not to observe that God is indignant and angry as often as human tradition relaxes and passes by the divine precepts … for custom without truth is the antiquity of error.

Cyprian, Epistle 73:3,9

In contrast, he also says this about “divine tradition”:

…you must diligently observe and keep the practice delivered from divine tradition and apostolic observance, which is also maintained among us, and almost throughout all the provinces

Cyprian, Epistle 67:5

There is actually much said about apostolic traditions which were handed down to the bishops and churches by the Apostles themselves, and which were followed and contrasted with the Scriptures that those same apostles wrote. Tradition wasn’t blindly accepted in the early church, but only followed if it could be shown to have originated with apostolic teaching, either by word or by letter; and if it were by word, it was checked against Scripture to make sure it was all in harmony.

That doesn’t necessarily mean they looked for “chapter and verse” (since chapter and verses didn’t exist in Scripture fully until 1553), but to see if what was being taught was consistent with the principles behind what was written down by the Apostles.

Let's explore a few examples of how Apostolic tradition was understood:

If then, any one who had attended on the elders came, I asked minutely after their sayings—what Andrew or Peter said, or what was said by Philip, or by Thomas, or by James, or by John, or by Matthew, or by any other of the Lord's disciples: which things Aristion and the presbyter John, the disciples of the Lord, say. For I imagined that what was to be got from books was not so profitable to me as what came from the living and abiding voice.

Just in this short quote from Papias (a bishop of Hierapolis, c. 70-163 AD), it displays that there was a value in seeking after those who had had direct contact with the source, and that was the preferred method over reading what was in books, to make sure that what they learned was as accurate as possible.

But, again, when we refer them (the Gnostics/heretics) to that tradition which originates from the apostles, [and] which is preserved by means of the succession of presbyters in the Churches, they object to tradition, saying that they themselves are wiser not merely than the presbyters, but even than the apostles

Irenaeus, Against Heresies III, 2:2

If something was handed down and received from the Apostles, it was held in high regard and used as a means to defeat heresies which often tried to creep into the Church and corrupt the faith. This is also the purpose of the creeds (see 1 Cor 15:3-7 for the earliest type of New Testament creed; or the Apostle’s Creed and Nicene Creed for later adaptations).

Irenaeus talks a lot about the traditions handed down in his Against Heresies, and as a bishop himself, took this responsibility very seriously to keep that which he had received “by … succession, the ecclesiastical tradition from the apostles … which has been preserved in the church from the apostles until now” (Against Heresies III, 3:3).

Basically, whatever the Apostles taught and did, that was Apostolic Tradition!

The early Christians who were close to the time of the Apostles, relied on this tradition for their learning in not only the faith, but in how to go about “doing church” and as a means to settle any disputes that arose over certain things which weren’t written down. They still had available to them churches which were founded or led by apostles, and so could enquire of them, or those who succeeded the apostolic bishop.

The Church in Ephesus, founded by Paul, and having John remaining among them permanently until the times of Trajan, is a true witness of the tradition of the apostles.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies III, 3:3

Suppose there arise a dispute relative to some important question among us, should we not have recourse to the most ancient Churches with which the apostles held constant intercourse, and learn from them what is certain and clear in regard to the present question? For how should it be if the apostles themselves had not left us writings? Would it not be necessary, [in that case,] to follow the course of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they did commit the Churches?

Irenaeus, Against Heresies III, 4:1

The expectation was that anyone could consult the ancient, apostle founded churches, and learn from them the things which had been taught – especially in cases where it concerned something that hadn’t been written down, and learn the truth. But not only learn it, but be able to fully trust it because of its long preserved, historical ties back to the apostles themselves.

In cases where there were people that had been directly taught by the apostles still around, or who had left writings on what they were taught, this was also preferential to learning the traditions of the apostles.

In this line of thinking, Irenaeus, again, speaks highly of Polycarp as one who could be relied on to learn about the apostles and their teachings, as he had faithfully handed these things on to those who succeeded him.

But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna … having always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down … to these things all the Asiatic Churches testify, as do also those men who have succeeded Polycarp down to the present time.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies III, 3:4

But in the case where someone couldn’t directly speak with a bishop from one of these churches, letters which were still in existence were favoured:

There is also a very powerful Epistle of Polycarp written to the Philippians, from which those who choose to do so, and are anxious about their salvation, can learn the character of his faith, and the preaching of the truth.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies III, 3:4

And the amazing thing is, we still have Polycarp’s letter today! It has survived and been preserved by the Church for over 2000 years, so we can still learn from him today as one who “would speak of the conversations he had held with John and with others who had seen the Lord” (a description by Irenaeus, who knew Polycarp).

What about the Bible?

Scripture was canonised to preserve and teach the basics of the Gospel and the way of salvation. Not everything that was written was canonised but certain other texts were held as important for teaching within the early church

The dependence on other people in the church body for learning and interpretation possibly came from taking those with the teaching gift seriously as Spirit led individuals, which Scripture expects (James 3:1; 1 Tim 3:2), and also from an understanding of Peter’s epistle warning against just making up your own interpretations:

2 Peter 1:20

First of all you must understand this, that no prophecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation

Just as Jesus didn't write anything down, but taught his disciples personally, they also taught people in the same way, mainly orally and in person, and wrote few things down when the occasion presented itself. Their followers then wrote down the things which they learned from the Apostles instead, probably more so as the Church grew and as time went on, to better preserve all they had learnt.

If we look at Hebrews, we can see what the basic teaching is considered to be:

Hebrews 6:1-2

Therefore let us go on toward perfection, leaving behind the basic teaching about Christ, and not laying again the foundation: repentance from dead works and faith toward God, instruction about baptisms, laying on of hands, resurrection of the dead, and eternal judgment.

These things listed here were considered to be the “basic teaching about Christ” (and are basically a summary of much of the New Testament doctrine) which implies that there is more to learn apart from these things listed!

If we are serious about our faith and learning all we can in order to fully walk in the way of Christ and his Apostles, then we must consult our forefathers in the faith and learn from them, just as they learned from those who preceded them, and those before them all the way back to the Apostles and Christ himself.

The New Testament letters and Gospels serve as a basis for our faith and doctrine, and as an introduction to the traditions of the Apostles as we can see the things they did and said, and what they taught the churches. But Christianity didn’t (and doesn’t) stop with the New Testament. Jesus himself promised the Holy Spirit to us as a means to be taught more (Jn 14:26) so that we wouldn’t be left alone or have everything he taught, lost to the sands of time.

The truth of the Gospel and how believers should act and live, and how to conduct ourselves in Church gatherings, was tied closely to what the Apostles taught and those traditions of theirs which were handed down to the succession of Bishops in all the churches. These Bishops and church leaders wrote many things which we can learn from, and better understand our faith in light of apostolic tradition, many of whose letters still survive.

But why should we trust them?

Ever sceptical, we should check our sources as there were many forgeries and heretical sects rising up and also writing letters trying to push their agendas. Firstly, historical resources will tell us who is a legitimate author if the date of the letter actually matches the lifespan of the claimed author. Not only that, other historical sources will validate certain people – such as Irenaeus validating Polycarp (and many others) when he makes a list of Bishops in the churches, all whom link back to the apostles. Then we have the vast resources of early Christian writers who took it on themselves to preserve and verify older texts to show which ones were truly written by an Apostle or by “apostolic men” as Tertullian calls them (Prescription against Heretics, ch. 32), meaning the companions of the apostles, like Luke and Mark or Clement (Phil 4:3).

Other than Polycarp’s letter, some of these other texts were so highly regarded and read in the early church, that some were included in early lists of canonical books, possibly due to their close ties with apostles, such as: the Epistle of Barnabas and 1 Clement. Later on, other books such as the Letter to Diognetus; the Shepherd of Hermas and the Didache were also included or widely read and used for teaching.

Better still, all of these texts still survive today and can be read and consulted as a modern way to seek to learn from apostolic tradition, since we can no longer just pop to the Ephesus church and enquire after the things John taught, or go to Corinth and ask after the things Paul which weren’t written down. You can view each of these letters by clicking the corresponding links above.

The references to apostolic traditions and the writings of those who followed and succeeded the apostles in the churches they founded are many. These texts make up a much larger collection than the New Testament, which just goes to show in itself that there was much more to be said and expounded on about the faith which many of us are unaware of.

Many questions that arise from reading the Scriptures have been dealt with quite thoroughly by the early Christians and church leaders and we’d do well to invest time in learning from them too.

So, as John Wesley puts it, “can anyone … be excused if they do not add to that learning the reading of the Fathers? The Fathers are the most authentic commentators on Scripture, for they were nearest the fountain and were eminently endued with that Spirit by whom all Scripture was given.”.

Happy reading!

Further Reading

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/050673.htm

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chapters_and_verses_of_the_Bible#Verses

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0125.htm

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papias_of_Hierapolis

- http://www.ntrf.org/articles/article_detail.php?PRKey=8

- http://www.christian-history.org/apostolic-tradition.html

- http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.iv.i.html

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0311.htm

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0101.htm

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0201.htm

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0714.htm

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0124.htm

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1010.htm

- http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/050667.htm

- http://earlychurch.com/JohnWesley.php

- https://www.ccel.org/creeds/apostles.creed.html

- https://www.ccel.org/creeds/nicene.creed.html

- https://patristics.info/epistle-of-polycarp-to-the-philippians.html

- https://thesacredfaith.co.uk/home/perma/1559484660/article/creedal-christians-the-nicene-creed.html

- https://thesacredfaith.co.uk/home/perma/1539286980/article/creedal-christians-the-apostles-creed.html

- How To Read The Bible For All It's Worth | FaithGiant

Leave a comment Like Back to Top Seen 13.6K times Liked 1 times

Enjoying this content?

Support my work by becoming a patron on Patreon!

By joining, you help fund the time, research, and effort that goes into creating this content — and you’ll also get access to exclusive perks and updates.

Even a small amount per month makes a real difference. Thank you for your support!

Recent Posts

Luke J. Wilson | 6 days ago | Blogging

As we commemorated the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation this year, the familiar image of Martin Luther striding up to the church door in Wittenberg — hammer in hand and fire in his eyes — has once again taken centre stage. It’s a compelling picture, etched into the imagination of many. But as is often the case with historical legends, closer scrutiny tells a far more nuanced and thought-provoking story. The Myth of the Door: Was the Hammer Ever Raised? Cambridge Reformation scholar Richard Rex is one among several historians who have challenged the romanticised narrative. “Strangely,” he observes, “there’s almost no solid evidence that Luther actually went and nailed them to the church door that day, and ample reasons to doubt that he did.” Indeed, the first image of Luther hammering up his 95 Theses doesn’t appear until 1697 — over 180 years after the fact. Eric Metaxas, in his recent biography of Luther, echoes Rex’s scepticism. The earliest confirmed action we can confidently attribute to Luther on 31 October 1517 is not an act of public defiance, but the posting of two private letters to bishops. The famous hammer-blow may never have sounded at all. Conflicting Accounts Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s successor and first biographer, adds another layer of complexity. He claimed Luther “publicly affixed” the Theses to the door of All Saints’ Church, but Melanchthon wasn’t even in Wittenberg at the time. Moreover, Luther himself never mentioned posting the Theses publicly, even when recalling the events years later. Instead, he consistently spoke of writing to the bishops, hoping the matter could be addressed internally. At the time, it was common practice for a university disputation to be announced by posting theses on church doors using printed placards. But no Wittenberg-printed copies of the 95 Theses survive. And while university statutes did require notices to be posted on all church doors in the city, Melanchthon refers only to the Castle Church. It’s plausible Luther may have posted the Theses later, perhaps in mid-November — but even that remains uncertain. What we do know is that the Theses were quickly circulated among Wittenberg’s academic elite and, from there, spread throughout the Holy Roman Empire at a remarkable pace. The Real Spark: Ink, Not Iron If there was a true catalyst for the Reformation, it wasn’t a hammer but a printing press. Luther’s Latin theses were swiftly reproduced as pamphlets in Basel, Leipzig, and Nuremberg. Hundreds of copies were printed before the year’s end, and a German translation soon followed, though it may never have been formally published. Within two weeks, Luther’s arguments were being discussed across Germany. The machinery of mass communication — still in its relative infancy — played a pivotal role in what became a theological, political, and social upheaval. The Letters of a Conscientious Pastor Far from the bold revolutionary of popular imagination, Luther appears in 1517 as a pastor deeply troubled by the abuse of indulgences, writing with respectful concern to those in authority. In his letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, he humbly addresses the archbishop as “Most Illustrious Prince,” and refers to himself as “the dregs of humanity.” “I, the dregs of humanity, have so much boldness that I have dared to think of a letter to the height of your Sublimity,” he writes — hardly the voice of a man trying to pick a fight. From Whisper to Roar Luther’s initial appeal through formal channels was, predictably, ignored. He was advised not to make trouble. But as opposition mounted and corruption remained unchecked, the once quiet reformer grew louder. His theological convictions deepened, and his public persona evolved. The lion did eventually roar — but not on October 31. A Catholic Reformer, Not a Protestant Founder It’s vital to remem...

Luke J. Wilson | 20th May 2025 | Islam

You are not alone. Around the world, many Muslims — people who already believe in one God, pray, and seek to live righteously — are drawn to know more about Jesus (ʿĪsā in Arabic). Some have heard He is more than a prophet. Some have sensed His presence in a dream or vision. And some simply long to know God more deeply, personally, and truly. So what does it mean to become a Christian? And how can you take that step? This guide is for you. 1. What Christians Believe About God and Jesus ➤ One God, Eternal and Good Christians believe in one God — the same Creator known to Abraham, Moses, and the prophets. But we also believe God is more personal and relational than many realise. In His love, He has revealed Himself as Father, Son (Jesus), and Holy Spirit — not three gods, but one God in three persons. ➤ Jesus Is More Than a Prophet Muslims honour Jesus as a great prophet, born of the virgin Mary. Christians also affirm this — but go further. The Bible teaches that Jesus is the Word of God (Kalimat Allāh), who became flesh to live among us. He performed miracles, healed the sick, raised the dead — and lived without sin.Jesus came not just to teach but to save — to bring us back to God by bearing our sins and rising again in victory over death. 2. Why Do We Need Saving? ➤ The Problem: Sin All people — no matter their religion — struggle with sin. We lie, get angry, feel jealous, act selfishly, or fail to love God fully. The Bible says: “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” (Romans 3:23) Sin separates us from God. And no matter how many good deeds we do, we can never make ourselves perfect or holy before Him. ➤ The Solution: Jesus Because God loves us, He did not leave us in our sin. He sent Jesus, His eternal Word, to live as one of us. Jesus died willingly, offering His life as a sacrifice for our sins, then rose again on the third day. “But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us.” (Romans 5:8) 3. How Do I Become a Christian? Becoming a Christian is not about joining a Western religion. It’s about entering a relationship with God through faith in Jesus Christ. Here is what the Bible says: ✝️ 1. Believe in Jesus Believe that Jesus is the Son of God, that He died for your sins, and that He rose again. “If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” (Romans 10:9) 💔 2. Repent of Your Sins Turn away from sin and ask God to forgive you. This is called repentance. It means being truly sorry and choosing a new way. “Repent therefore, and turn to God so that your sins may be wiped out.” (Acts 3:19) 💧 3. Be Baptised Jesus commands His followers to be baptised in water as a sign of their new life. Baptism represents washing away your old life and rising into a new one with Jesus. “Repent and be baptised every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven.” (Acts 2:38) 🕊️ 4. Receive the Holy Spirit When you believe in Jesus, God gives you the Holy Spirit to live within you, guiding you, comforting you, and helping you follow His will. “You received the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Romans 8:15) 🧎 5. Begin a New Life As a Christian, you are born again — spiritually renewed. You begin to grow in faith, love, and holiness. You read the Bible, pray, fast, and gather with other believers. Your life is no longer your own; you now live for God. 4. What Does a Christian Life Look Like? Jesus said: “If anyone wants to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” (Matthew 16:24) This means: Loving God with all your heart Loving your neighbour — even your enemies Forgiving others ...

Luke J. Wilson | 05th May 2025 | Politics

When we think about David and Saul, we often focus on David’s rise to kingship or his battle with Goliath. But hidden within that story is a deep lesson for today’s generation about leadership, resistance, and the power of revolutionary love. At a recent youth training event (thanks to South West Youth Ministries), I was asked how I would present the story of David and Saul to a Christian teenage youth group. My mind turned to the politics of their relationship, and how David accepted Saul’s leadership, even when Saul had gone badly astray. David recognised that Saul was still God’s anointed king — placed there by God Himself — and that it was not David’s place to violently remove him. Gen-Z are more politically aware and engaged than previous generations, and are growing up in a world where politics, leadership, and social issues seem impossible to escape. We live in a world where political leaders — whether Trump, Putin, Starmer, or others — are often seen as examples of failed leadership. It’s easy to slip into bitterness, cynicism, or violent rhetoric. These kids are immersed in a culture of activism and outrage. As Christians, we’re called to care deeply about truth and justice and approach leadership differently from the world around us (Hosea 6:6; Isaiah 1:17; Micah 6:8). The story of David and Saul offers pertinent lessons for our modern lives. Respect Without Endorsement David’s respect for Saul was not blind loyalty. He did not agree with Saul’s actions, nor did he ignore Saul’s evil. David fled from Saul’s violence; he challenged Saul’s paranoia; he even cut the corner of Saul’s robe to prove he had the chance to kill him but chose not to. Yet throughout, David refused to take matters into his own hands by force. Why? Because David understood that even flawed authority ultimately rested in God’s hands, he trusted that God would remove Saul at the right time. This is echoed later in the New Testament when Paul writes in Romans 13 that “there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God”, something even Jesus reminded Pilate of during his trial (John 19:10–11). In other words, even flawed leadership can be part of God’s bigger plan, whether for blessing or discipline. Even when leaders go bad, our call as believers is to maintain integrity, respect the position, and resist evil through righteousness — not rebellion. David and Saul: A Lesson in Respect and Restraint Saul was Israel’s first king — anointed by God but later corrupted by pride, fear, and violence. David, chosen to succeed him, spent years running for his life from Saul’s jealous rage. One day, David found Saul alone and vulnerable in a cave. His men urged him to strike Saul down and end the conflict. But David refused: “I will not raise my hand against my lord; for he is the Lord’s anointed.” (1 Samuel 24:10) Instead of killing Saul, David cut off a piece of his robe to prove he could have harmed him, but didn’t. In doing so, he demonstrated a real form of nonviolent resistance. He stood firm against Saul’s injustice without resorting to injustice himself, and acted in a way that could try to humble Saul instead. Peacemaking Is Not Passivity There is a modern misconception that peacemaking means doing nothing and just letting injustice roll all over us. But true biblical peacemaking is not passive; it actively resists evil without becoming evil. Interestingly, David’s actions toward Saul also foreshadow the type of nonviolent resistance Jesus later taught. When Jesus commanded His followers to turn the other cheek, go the extra mile, and love their enemies, he was not calling for passive submission but offering what scholar Walter Wink describes as a “third way” — a bold, peaceful form of resistance that uses what he calls “moral jiu-jitsu” to expose injustice without resorting to violenc...

Luke J. Wilson | 21st April 2025 | Easter

Over the years, I’ve encountered many Christians who’ve quoted from Alexander Hislop’s The Two Babylons as if it were a solid historical resource. The book claims that the Roman Catholic Church is not truly Christian but rather a continuation of ancient Babylonian religion. It’s self-assured and sweeping, and for many people, it seems to explain everything, from Marian devotion to Lent and Easter, to Christmas, as rooted in paganism. But is it accurate? In short: no, it really isn’t. Hislop’s work is a classic example of 19th-century pseudohistory — a polemical piece, written to prove a point, not to explore any historical truth. Flawed Methods and Wild Claims Hislop argues that most Catholic practices — from the Mass and clerical robes to festivals like Christmas and Easter — were somehow borrowed from Babylonian religion. The problem being that Hislop doesn’t rely on primary sources or credible historical data. Instead, he draws connections based on word similarities (like Easter and Ishtar) or visual resemblances (like Mary and child compared with mother-goddess statues from ancient cultures). But phonetic resemblance isn’t evidence, and neither is visual similarity. For example, if I say “sun” and “son” in English, they may sound alike, but they aren’t the same thing. That’s the level of reasoning at work in much of The Two Babylons. Hislop often lumps together completely different ancient figures — Isis, Semiramis, Ishtar, Aphrodite — as if they were all just variations of the same deity. He then tries to say Mary is just the Christian version of this pagan goddess figure. But there’s no credible evidence for that at all. Mary is understood through the lens of Scripture and Christian theology, not through pagan myth. The earliest depictions of Mary and the Christ-child date back to the second century and do not resemble any of the pagan idols. But, again, the common accusations are based on superficial similarities of a woman nursing a child. That’s going to look the same no matter who or what does that! Oldest depiction of Mary. Dura-Europos Church, Syria, 2nd century What About Lent and Tammuz? One of Hislop’s more popular claims is that Lent comes from a Babylonian mourning ritual for the god Tammuz, mentioned in Ezekiel 8:14. He argues that early Christians borrowed the 40-day mourning period and just rebranded it. But this doesn’t line up with the evidence. Lent developed as a time of fasting and repentance leading up to Easter — especially for new believers preparing for baptism. The number forty comes from Scripture: Jesus’ forty days in the wilderness, Moses’ fast on Sinai, and Elijah’s journey to Horeb. Church Fathers like Irenaeus and Athanasius saw it as a time for self-denial and spiritual renewal — not mourning a pagan god. Yes, there are pagan festivals that involve seasonal death and rebirth stories. But similarity does not mean origin. If that logic held, then even Jesus’ resurrection would be suspect because pagan cultures also told resurrection-like stories. Yet the gospel stands apart — not because of myth but because of history and revelation. Why Hislop’s Work Persists Even though The Two Babylons is poor scholarship, it’s unfortunately had a long shelf life. That’s partly because it appeals to a certain kind of suspicion. If you’re already sceptical about the Catholic Church, Hislop offers an easy explanation: “It’s all pagan!”. But history isn’t ever that simple. And theology — especially the theology handed down through the ages by the faithful— isn’t built on conspiracy and apparent obscure connections, but on Christ and the truth of the Scriptures. Interestingly, even Ralph Woodrow, a minister who once wrote a book defending Hislop’s ideas, later retracted his views after digging deeper into the evidence. He eventually wrote a book called The Babylon Connect...