┬Ā

Biblical Inspiration and the Canon: How We Got the Bible

The Bible is often described as ŌĆ£God-breathed,ŌĆØ a phrase taken from 2 Timothy 3:16: ŌĆ£All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness.ŌĆØ But what does it mean for Scripture to be ŌĆ£inspired,ŌĆØ and how did the books of the Bible come to be recognised as part of the canonŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖthe authoritative collection of writings that make up the Bible? Were they really ŌĆ£decidedŌĆØ at the Council of Nicaea, as some popular myths claim?

Table of Contents

Understanding Biblical Inspiration

A helpful analogy for inspiration is that of an architect designing a great building. Consider St. PaulŌĆÖs Cathedral in LondonŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖChristopher Wren was the architect who planned and designed it, yet he himself did not lay a single brick. Instead, countless workers followed his design to bring the cathedral into existence. Similarly, God is the ultimate author of Scripture, yet He worked through human writers to bring His message to us. The Holy Spirit inspired them, guiding their words while allowing their personalities, historical context, and literary style to remain evident in their writings.

This means that while the Bible is written by human hands, it carries divine authority because its true source is God Himself. The process of inspiration does not mean God dictated each word like a secretary taking notes, or by possessing the authors, but rather that He ensured the truth of His message was faithfully recorded by the biblical writers.

What is the┬ĀCanon?

The word ŌĆ£canonŌĆØ comes from the Greek ╬║╬▒╬ĮŽÄ╬Į (kan┼Źn), meaning ŌĆ£ruleŌĆØ or ŌĆ£measuring rod.ŌĆØ In the context of the Bible, the canon refers to the official list of books recognised as divinely inspired and authoritative for faith and practice.

The canon developed over time as the early church recognised which writings carried divine authority. The Old Testament canon was largely settled by the time of Jesus, based on the Hebrew Scriptures used in the Jewish community. The New Testament canon, however, was formed through a process of discernment over several centuries, as the church recognised which writings were truly inspired and authoritative.

The Septuagint and the Deuterocanonical Books

The Septuagint (LXX) is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, produced in the 3rd-2nd centuries BC. It was widely used by Greek-speaking Jews and later by early Christians, including the apostles. The Septuagint included several books not found in the Hebrew Bible, known as the Deuterocanonical books (such as Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, and 1ŌĆō2 Maccabees). While these books were accepted in many early Christian communities and remain part of the canon in Catholic and Orthodox traditions, Protestant reformers later removed them, considering them useful but not divinely inspired at the same level as the rest of Scripture.

The reformersŌĆÖ view was influenced by Jerome, who, in the 4th century, argued that these books were not part of the Hebrew Bible and therefore should be considered separate. However, he still included them in his Latin Vulgate translation, recognising their historical and devotional value. The Reformers followed JeromeŌĆÖs stance, moving these books into a separate section rather than outright removing them. It was not until the 19th century that an American Bible Society, citing printing costs and other practical considerations, physically removed these books entirely from Protestant Bibles. This decision solidified what is now commonly referred to as the ŌĆ£Protestant canonŌĆØ of 66 books.

And the other Books (as Hierome saith) the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrineŌĆ”

(Article 6, 39 Articles of Religion, AD┬Ā1562)

How Were the Books of the Bible Selected?

For a book to be included in the New Testament canon, it needed to meet certain criteria:

- Apostolic Authorship or ConnectionŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖThe book had to be written by an apostle or someone directly connected to an apostle. For example, the Gospel of Mark was accepted because Mark was closely associated with Peter, and according to Papias (as recorded by Eusebius in Ecclesiastical History 3.39.15ŌĆō16), Mark wrote his Gospel based on PeterŌĆÖs preaching.

- Theological ConsistencyŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖThe book had to align with the teachings of Jesus and the apostles. A text was not included if a text contained theological ideas that contradicted the established apostolic message.

- Widespread Use and AcceptanceŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖThe book had to be widely recognised and used by the early Christian community as authoritative.

- Divine InspirationŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖThe early church recognised that certain writings carried the authority of God, often demonstrated through their spiritual impact and consistency with the rest of Scripture.

Why Were Some Books Excluded?

Some early Christian writings, such as 1 Clement and the Epistle of Barnabas, were highly respected but ultimately not included in the New Testament. Why?

- 1 Clement was written by Clement of Rome, an early church leader likely taught by the apostles. However, it was more of a pastoral letter encouraging church unity rather than a divinely inspired revelation. While it was highly valued, it did not carry the same apostolic authority as the New Testament writings.

- The Epistle of Barnabas was traditionally attributed to Barnabas, PaulŌĆÖs companion, but its authorship is uncertain. Additionally, it contains theological interpretations that go beyond apostolic teaching, particularly in its extreme allegorical reading of the Old Testament.

A key distinction between these writings and books like Luke and Acts is that Luke was recording the testimony of the apostles themselves under their oversight. Even though he was not an apostle, he wrote with direct apostolic authority. In contrast, 1 Clement and Barnabas were secondary reflections on Christian teaching rather than inspired Scripture.

Has the Bible Been Edited or Corrupted Over┬ĀTime?

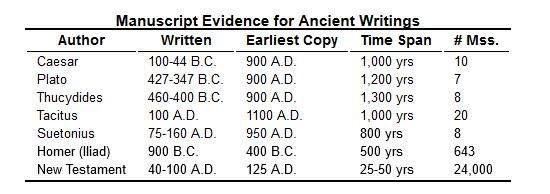

Some claim that the Bible has been altered or corrupted over the centuries, making it unreliable. However, the sheer number of surviving New Testament manuscripts allows us to reconstruct the original text with a high degree of confidence.

- We possess over 5,800 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, along with thousands more in Latin, Syriac, and other languages.

- Among these, we have fragments from the second century, including Papyrus 52 (P52), a small portion of JohnŌĆÖs Gospel dating to around AD 125.

- By the fourth century, we have complete copies of the New Testament, such as Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus.

With this wealth of manuscript evidence, scholars can compare variations and confidently determine what the original text said.

Bart Ehrman, a notable agnostic New Testament scholar and textual critic, acknowledges this in his book Misquoting Jesus:

ŌĆ£If he (Bruce Metzger) and I were put in a room and asked to hammer out a consensus statement on what we think the original text of the New Testament probably looked like, there would be very few points of disagreementŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖmaybe one or two dozen out of many thousands.┬ĀŌĆ” [T]he essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.ŌĆØ

Bruce Metzger, ErhmanŌĆÖs mentor, was a leading and influential New Testament scholar and textual critic of the 20th century.

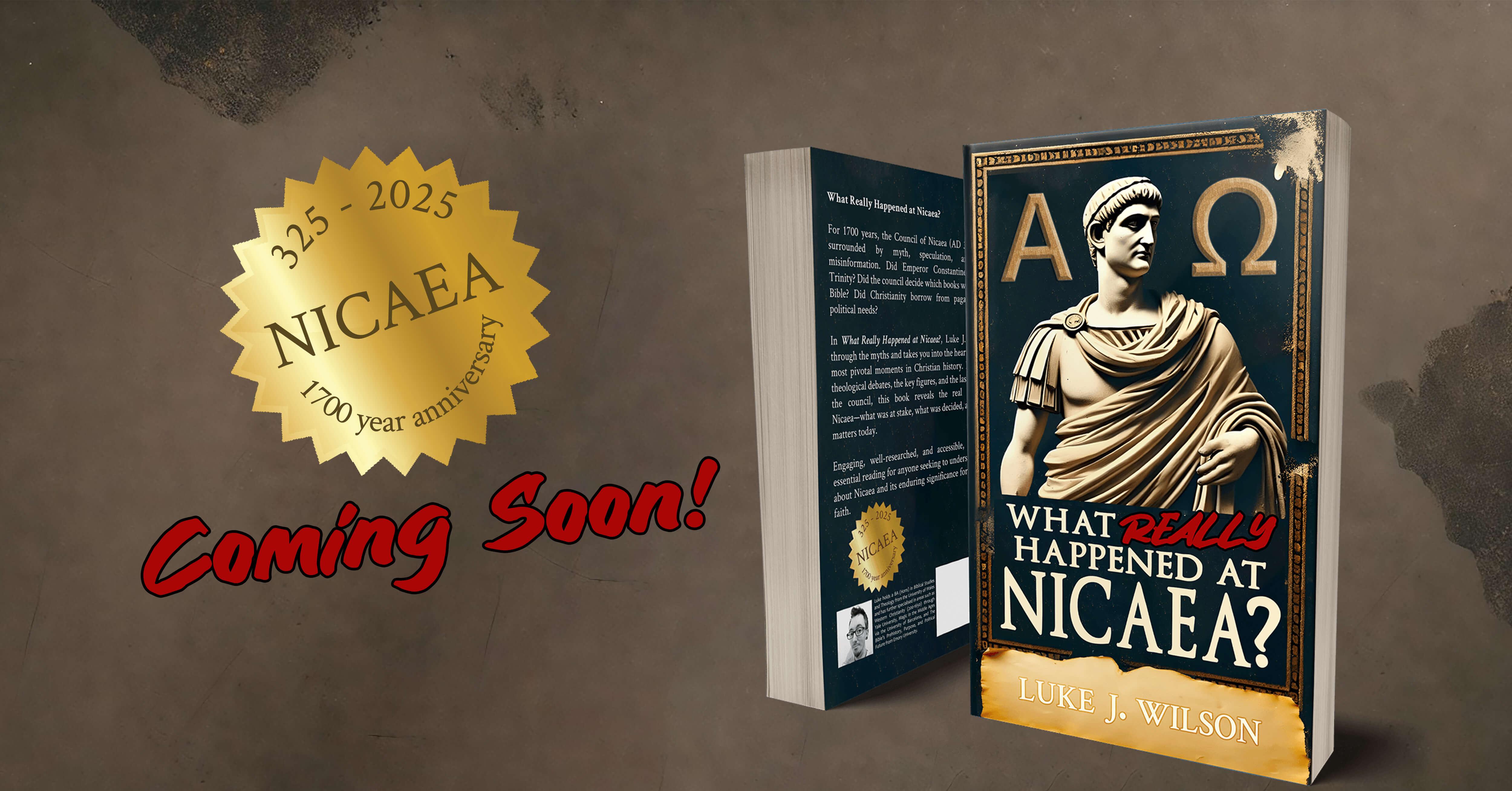

Did the Church Decide the Canon at┬ĀNicaea?

A common misconception is that the Church, particularly at the Council of Nicaea (AD 325), decided which books to include in the Bible while suppressing others. Some versions of the myth claim that the bishops at Nicaea placed all the books on a table and let God miraculously shake off the ones He did not want included. This myth can be traced back to a late ninth-century Greek manuscript known as the Synodicon Vetus. This manuscript, claiming to summarise decisions from Greek councils, presented a narrative in which a divine miracle occurred at Nicaea, with the canonical books being placed on a table while the apocryphal ones fell beneath it.

The canonical and apocryphal books it distinguished in the following manner: in the house of God the books were placed down by the holy altar; then the council asked the Lord in prayer that the inspired works be found on top and the spurious on the bottom. (Synodicon Vetus,┬Ā35)

This account was later repeated by figures such as Voltaire in the 18th century, who further fuelled the misconception in his Philosophical Dictionary. It was revived again in the 19th century by Christian radical Robert Taylor, cementing the false idea that Nicaea determined the canon.

In reality, Nicaea had nothing to do with the formation of the canon. The books of the New Testament were already widely accepted based on their apostolic origin, theological soundness, and use in worship long before Nicaea convened.

Conclusion

The Bible is not a random collection of ancient writings but a carefully recognised collection of divinely inspired texts. God, the ultimate architect, ensured that His message was faithfully recorded and preserved through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. The process of canonisation was not about choosing which books people liked best but about discerning which books bore the mark of divine inspiration and apostolic authority.

Understanding this helps us appreciate the Bible not just as a historical document but as the living and active Word of God, given to guide us in faith and life.

Further Reading

- Debunking the Myth: The Council of Nicaea and the Formation of the Biblical Canon

- How Polycarp (And Others) Show The Early Use Of The New Testament

- Understanding The New Testament: Inspiration, Canonisation, And Historical Context

- Articles of Religion | The Church of England

- Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (Plus): Amazon.co.uk: Bart D. Ehrman: 9780060859510: Books

- PaulŌĆÖs Lost Letters, Michael S. Heiser

- My Mentor Bruce MetzgerŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖThe Bart Ehrman Blog

- AntilegomenaŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖWikipedia

- Bruce M. MetzgerŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖWikipedia

- Bart D. EhrmanŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖWikipedia

┬Ā

Leave a comment Like Back to Top Seen 729 times Liked 0 times

Enjoying this content?

Support my work by becoming a patron on Patreon!

By joining, you help fund the time, research, and effort that goes into creating this content ŌĆö and youŌĆÖll also get access to exclusive perks and updates.

Even a small amount per month makes a real difference. Thank you for your support!

Subscribe to Updates

If you enjoyed this, why not subscribe to free email updates and join over 864 subscribers today!

My new book is out now! Order today wherever you get books

Recent Posts

Luke J. Wilson | 19th August 2025 | Fact-Checking

A poetic post has been circulating widely on Facebook, suggesting that our anatomy mirrors various aspects of Scripture. On the surface it sounds inspiring, but when we take time to weigh its claims, two main problems emerge. The viral post circulating on┬ĀFacebook [Source] First, some of its imagery unintentionally undermines the pre-existence of Christ, as if Jesus only ŌĆ£held the earth togetherŌĆØ for the 33 years of His earthly life. Second, it risks reducing the resurrection to something like biological regeneration, as if Jesus simply restarted after three days, instead of being raised in the miraculous power of God. Alongside these theological dangers, many of the scientific claims are overstated or symbolic rather than factual. LetŌĆÖs go through them one by one. 1. ŌĆ£Jesus died at 33. The human spine has 33 vertebrae. The same structure that holds us up is the same number of years He held this┬ĀEarth.ŌĆØ The human spine does generally have 33 vertebrae, but that number includes fused bones (the sacrum and coccyx), and not everyone has the same count. Some people have 32 or 34. More importantly, the Bible never says Jesus was exactly 33 when He diedŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖLuke tells us He began His ministry at ŌĆ£about thirtyŌĆØ (Luke 3:23), and we know His public ministry lasted a few years, but His precise age at death is a tradition, not a biblical statement. See my other recent article examining the age of Jesus here. Theologically, the phrase ŌĆ£the same number of years He held this EarthŌĆØ is problematic. Jesus did not hold the world together only for 33 years. The eternal Word was with God in the beginning (John 1:1ŌĆō3), and ŌĆ£in Him all things hold togetherŌĆØ (Colossians 1:17). Hebrews says He ŌĆ£sustains all things by His powerful wordŌĆØ (Hebrews 1:3). He has always upheld creation, before His incarnation, during His earthly ministry, and after His resurrection. To imply otherwise is to risk undermining the pre-existence of Christ. 2. ŌĆ£We have 12 ribs on each side. 12 disciples. 12 tribes of Israel. God built His design into our┬Ābones.ŌĆØ Most people do have 12 pairs of ribs, though some are born with an extra rib, or fewer. The number 12 is certainly biblical: the 12 tribes of Israel (Genesis 49), the 12 apostles (Matthew 10:1ŌĆō4), and the 12 gates and foundations of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21). But thereŌĆÖs no biblical connection between rib count and these symbolic twelves. This is a case of poetic association, not design woven into our bones. The only real mention of ribs in Scripture is when Eve is created from one of AdamŌĆÖs ribs in Genesis 2:21ŌĆō22, which has often led to the teaching in some churches that men have one less rib than women (contradicting this new claim)! 3. ŌĆ£The vagus nerve runs from your brain to your heart and gut. It calms storms inside the body. It looks just like a┬Ācross.ŌĆØ The vagus nerve is real and remarkable. It regulates heart rate, digestion, and helps calm stress, and doctors are even using vagus nerve stimulation as therapy for epilepsy, depression, and inflammation showing it really does ŌĆ£calm stormsŌĆØ in the body.┬ĀBut it does not look like a cross anatomically. The language about ŌĆ£calming stormsŌĆØ may echo the way Jesus calmed the storm on the Sea of Galilee (Mark 4:39), but here again the poetic flourish stretches science (and Scripture) beyond whatŌĆÖs accurate. 4. ŌĆ£Jesus rose on the third day. Science tells us that when you fast for 3 days, your body starts regenerating. Old cells die. New ones are born. Healing begins. Your body literally resurrects itself.ŌĆØ ThereŌĆÖs a serious theological problem here. To equate JesusŌĆÖ resurrection with a biological ŌĆ£regenerationŌĆØ after fasting is to misrepresent what actually happened. Fasting can indeed trigger cell renewal and immune repair, but it cannot bring the dead back to life. ItŌĆÖs still a natural process that happens...

Luke J. Wilson | 08th July 2025 | Islam

ŌĆ£We all worship the same GodŌĆØ. Table of Contents 1) Where YHWH and Allah Appear┬ĀSimilar 2) Where AllahŌĆÖs Character Contradicts YHWHŌĆÖs┬ĀGoodness 3) Where Their Revelations Directly Contradict Each┬ĀOther 4) YHWHŌĆÖs Love for the Nations vs. AllahŌĆÖs Commands to Subjugate 5) Can God Be Seen? What the Bible and QurŌĆÖan┬ĀSay 6) Salvation by Grace vs. Salvation by┬ĀWorks Conclusion: Same God? Or Different Revelations? YouŌĆÖve heard it from politicians, celebrities, and even some pastors. ItŌĆÖs become something of a modern mantra, trying to shoehorn acceptance of other beliefs and blend all religions into one, especially the Abrahamic ones. But what if the Bible and QurŌĆÖan tell different stories? LetŌĆÖs see what their own words reveal so you can judge for yourself. This Tweet recently caused a stir on social┬Āmedia 1) Where YHWH and Allah Appear┬ĀSimilar Many point out that Jews, Christians, and Muslims share a belief in one eternal Creator God. ThatŌĆÖs trueŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖup to a point. Both the Bible and QurŌĆÖan describe God as powerful, all-knowing, merciful, and more. HereŌĆÖs a list comparing some of the common shared attributes between YHWH and Allah, with direct citations from both Scriptures: 26 Shared Attributes of YHWH and┬ĀAllah According to the Bible (NRSV) and the QurŌĆÖan Eternal YHWH: ŌĆ£From everlasting to everlasting you are God.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖPsalm 90:2 Allah: ŌĆ£He is the First and the LastŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 57:3 Creator YHWH: ŌĆ£In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖGenesis 1:1 Allah: ŌĆ£The Originator of the heavens and the earthŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 2:117 Omnipotent (All-Powerful) YHWH: ŌĆ£Nothing is too hard for you.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖJeremiah 32:17 Allah: ŌĆ£Allah is over all things competent.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 2:20 Omniscient (All-Knowing) YHWH: ŌĆ£Even before a word is on my tongue, O LORD, you know it.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖPsalm 139:4 Allah: ŌĆ£He knows what is on the land and in the seaŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 6:59 Omnipresent (Present Everywhere) YHWH: ŌĆ£Where can I go from your Spirit?ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖPsalm 139:7ŌĆō10 Allah: ŌĆ£He is with you wherever you are.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 57:4 Holy YHWH: ŌĆ£Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖIsaiah 6:3 Allah: ŌĆ£The Holy One (Al-Quddus).ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 59:23 Just YHWH: ŌĆ£A God of faithfulness and without injustice.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖDeuteronomy 32:4 Allah: ŌĆ£Is not Allah the most just of judges?ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 95:8 Merciful YHWH: ŌĆ£The LORD, merciful and graciousŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖExodus 34:6 Allah: ŌĆ£The Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 1:1 Compassionate YHWH: ŌĆ£As a father has compassion on his childrenŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖPsalm 103:13 Allah: ŌĆ£He is the Forgiving, the Affectionate.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 85:14 Faithful YHWH: ŌĆ£Great is your faithfulness.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖLamentations 3:22ŌĆō23 Allah: ŌĆ£Indeed, the promise of Allah is truth.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 30:60 Unchanging YHWH: ŌĆ£For I the LORD do not change.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖMalachi 3:6 Allah: ŌĆ£None can change His words.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 6:115 Sovereign YHWH: ŌĆ£The LORD has established his throne in the heavensŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖPsalm 103:19 Allah: ŌĆ£Blessed is He in whose hand is dominionŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 67:1 Loving YHWH: ŌĆ£God is love.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖ1 John 4:8 Allah: ŌĆ£Indeed, my Lord is Merciful and Affectionate (Al-Wadud).ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 11:90 Forgiving YHWH: ŌĆ£I will not remember your sins.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖIsaiah 43:25 Allah: ŌĆ£Allah forgives all sinsŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 39:53 Wrathful toward evil YHWH: ŌĆ£The LORD is a jealous and avenging GodŌĆ”ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖNahum 1:2 Allah: ŌĆ£For them is a severe punishment.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 3:4 One/Unique YHWH: ŌĆ£The LORD is one.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖDeuteronomy 6:4 Allah: ŌĆ£Say: He is Allah, One.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖSurah 112:1 Jealous of worship YHWH: ŌĆ£I the LORD your God am a jealous God.ŌĆØŌĆŖŌ...

Luke J. Wilson | 05th June 2025 | Blogging

As we commemorated the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation this year, the familiar image of Martin Luther striding up to the church door in WittenbergŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖhammer in hand and fire in his eyesŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖhas once again taken centre stage. ItŌĆÖs a compelling picture, etched into the imagination of many. But as is often the case with historical legends, closer scrutiny tells a far more nuanced and thought-provoking story. The Myth of the┬ĀDoor:┬ĀWas the Hammer Ever┬ĀRaised? Cambridge Reformation scholar Richard Rex is one among several historians who have challenged the romanticised narrative. ŌĆ£Strangely,ŌĆØ he observes, ŌĆ£thereŌĆÖs almost no solid evidence that Luther actually went and nailed them to the church door that day, and ample reasons to doubt that he did.ŌĆØ Indeed, the first image of Luther hammering up his 95 Theses doesnŌĆÖt appear until 1697ŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖover 180 years after the fact. Eric Metaxas, in his recent biography of Luther, echoes RexŌĆÖs scepticism. The earliest confirmed action we can confidently attribute to Luther on 31 October 1517 is not an act of public defiance, but the posting of two private letters to bishops. The famous hammer-blow may never have sounded at all. Conflicting Accounts Philip Melanchthon, LutherŌĆÖs successor and first biographer, adds another layer of complexity. He claimed Luther ŌĆ£publicly affixedŌĆØ the Theses to the door of All SaintsŌĆÖ Church, but Melanchthon wasnŌĆÖt even in Wittenberg at the time. Moreover, Luther himself never mentioned posting the Theses publicly, even when recalling the events years later. Instead, he consistently spoke of writing to the bishops, hoping the matter could be addressed internally. At the time, it was common practice for a university disputation to be announced by posting theses on church doors using printed placards. But no Wittenberg-printed copies of the 95 Theses survive. And while university statutes did require notices to be posted on all church doors in the city, Melanchthon refers only to the Castle Church. ItŌĆÖs plausible Luther may have posted the Theses later, perhaps in mid-NovemberŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖbut even that remains uncertain. What we do know is that the Theses were quickly circulated among WittenbergŌĆÖs academic elite and, from there, spread throughout the Holy Roman Empire at a remarkable pace. The Real Spark: Ink, Not┬ĀIron If there was a true catalyst for the Reformation, it wasnŌĆÖt a hammer but a printing press. LutherŌĆÖs Latin theses were swiftly reproduced as pamphlets in Basel, Leipzig, and Nuremberg. Hundreds of copies were printed before the yearŌĆÖs end, and a German translation soon followed, though it may never have been formally published. Within two weeks, LutherŌĆÖs arguments were being discussed across Germany. The machinery of mass communicationŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖstill in its relative infancyŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖplayed a pivotal role in what became a theological, political, and social upheaval. The Letters of a Conscientious Pastor Far from the bold revolutionary of popular imagination, Luther appears in 1517 as a pastor deeply troubled by the abuse of indulgences, writing with respectful concern to those in authority. In his letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, he humbly addresses the archbishop as ŌĆ£Most Illustrious Prince,ŌĆØ and refers to himself as ŌĆ£the dregs of humanity.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£I, the dregs of humanity, have so much boldness that I have dared to think of a letter to the height of your Sublimity,ŌĆØ he writesŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖhardly the voice of a man trying to pick a fight. From Whisper to┬ĀRoar LutherŌĆÖs initial appeal through formal channels was, predictably, ignored. He was advised not to make trouble. But as opposition mounted and corruption remained unchecked, the once quiet reformer grew louder. His theological convictions deepened, and his public persona evolved. The lion did eventually roarŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖbut not on October 31. A Catholic Reformer, Not a Protestant Founder ItŌĆÖs vital to remem...

Luke J. Wilson | 20th May 2025 | Islam

You are not alone. Around the world, many MuslimsŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖpeople who already believe in one God, pray, and seek to live righteouslyŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖare drawn to know more about Jesus (╩┐─¬s─ü in Arabic). Some have heard He is more than a prophet. Some have sensed His presence in a dream or vision. And some simply long to know God more deeply, personally, and truly. So what does it mean to become a Christian? And how can you take that step? This guide is for you. 1. What Christians Believe About God and Jesus Ō׿ One God, Eternal and Good Christians believe in one GodŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖthe same Creator known to Abraham, Moses, and the prophets. But we also believe God is more personal and relational than many realise. In His love, He has revealed Himself as Father, Son (Jesus), and Holy SpiritŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖnot three gods, but one God in three persons. Ō׿ Jesus Is More Than a Prophet Muslims honour Jesus as a great prophet, born of the virgin Mary. Christians also affirm thisŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖbut go further. The Bible teaches that Jesus is the Word of God (Kalimat All─üh), who became flesh to live among us. He performed miracles, healed the sick, raised the deadŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖand lived without sin.Jesus came not just to teach but to saveŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖto bring us back to God by bearing our sins and rising again in victory over death. 2. Why Do We Need Saving? Ō׿ The Problem: Sin All peopleŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖno matter their religionŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖstruggle with sin. We lie, get angry, feel jealous, act selfishly, or fail to love God fully. The Bible says: ŌĆ£All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.ŌĆØ (Romans 3:23) Sin separates us from God. And no matter how many good deeds we do, we can never make ourselves perfect or holy before Him. Ō׿ The Solution: Jesus Because God loves us, He did not leave us in our sin. He sent Jesus, His eternal Word, to live as one of us. Jesus died willingly, offering His life as a sacrifice for our sins, then rose again on the third day. ŌĆ£But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us.ŌĆØ (Romans 5:8) 3. How Do I Become a Christian? Becoming a Christian is not about joining a Western religion. ItŌĆÖs about entering a relationship with God through faith in Jesus Christ. Here is what the Bible says: Ō£Ø’ĖÅ 1. Believe in Jesus Believe that Jesus is the Son of God, that He died for your sins, and that He rose again. ŌĆ£If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.ŌĆØ (Romans 10:9) ¤Æö 2. Repent of Your Sins Turn away from sin and ask God to forgive you. This is called repentance. It means being truly sorry and choosing a new way. ŌĆ£Repent therefore, and turn to God so that your sins may be wiped out.ŌĆØ (Acts 3:19) ¤Æ¦ 3. Be Baptised Jesus commands His followers to be baptised in water as a sign of their new life. Baptism represents washing away your old life and rising into a new one with Jesus. ŌĆ£Repent and be baptised every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven.ŌĆØ (Acts 2:38) ¤ĢŖ’ĖÅ 4. Receive the Holy Spirit When you believe in Jesus, God gives you the Holy Spirit to live within you, guiding you, comforting you, and helping you follow His will. ŌĆ£You received the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry, ŌĆśAbba! Father!ŌĆÖŌĆØ (Romans 8:15) ¤¦Ä 5. Begin a New Life As a Christian, you are born againŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖspiritually renewed. You begin to grow in faith, love, and holiness. You read the Bible, pray, fast, and gather with other believers. Your life is no longer your own; you now live for God. 4. What Does a Christian Life Look Like? Jesus said: ŌĆ£If anyone wants to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.ŌĆØ (Matthew 16:24) This means: Loving God with all your heart Loving your neighbourŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖeven your enemies Forgiving others ...